"It's not drought, it's plunder" Querétaro, the valley of data centers

By Paola Ricaurte Quijano and Teresa Roldán Soria. Querétaro, MEXICO.

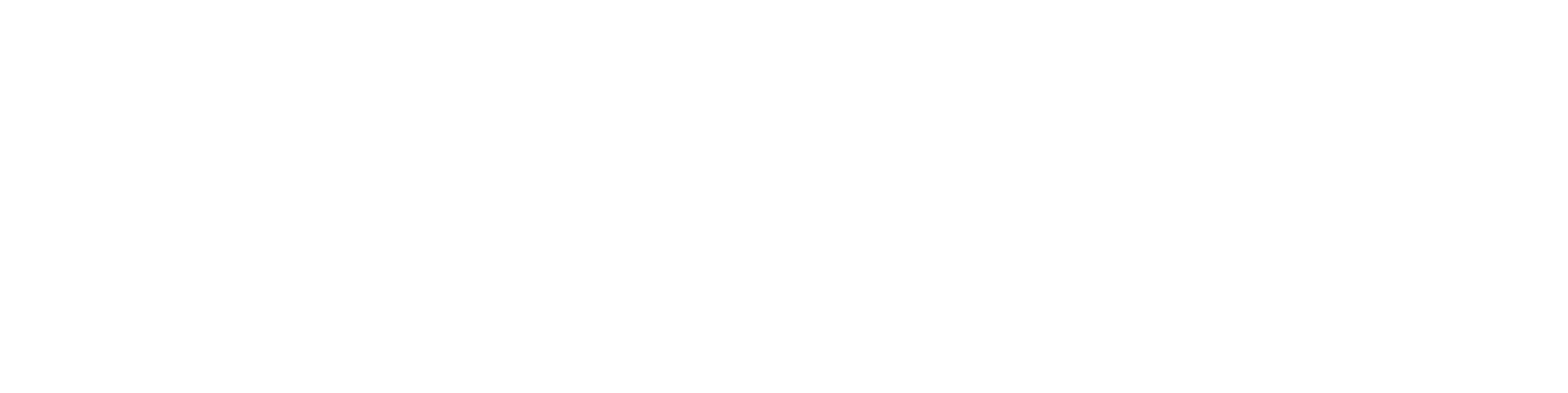

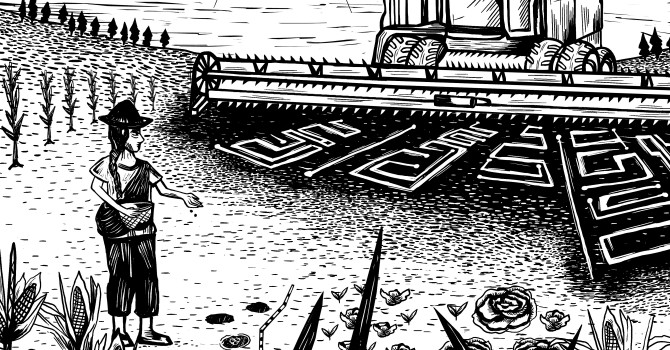

Illustration: Giovanna Joo

WATER

Introduction

The global boom of the data center industry, a trend driven by increased investment and deployment in Artificial Intelligence (AI), is resulting in distinct configurations within various local contexts. Across the majority world, geopolitical interests intersect with historic territorial dynamics. Querétaro, a state in north-central Mexico, is a paradigmatic example where these dynamics create tension between different actors: on one side, companies and governments, and on the other, the communities that inhabit these territories—particularly Indigenous peoples and campesinoI communities—and organized civil society.

This case demonstrates that the industry's plunder of the commons—a necessary part of AI's life cycle—is achieved through mechanisms of dispossession that perpetuate historical and colonial legacies in its underlying infrastructure. We must, therefore, analyze the diverse socio-environmental effects of data centers through a structural lens, as they are part of an emerging industry driven by a technological development model imposed by imperial powers.

By analyzing the data center industry in Querétaro, Mexico, this text offers a political-ecological, decolonial, and feminist critique. It examines the industry's impacts, the enduring forms of dispossession and community resistance, and the potential for interventions based on human rights and social justice. The data center phenomenon is inherently complex and we must therefore explore its historical, economic, geopolitical, legal, infrastructural, and environmental dimensions, but also the sociocultural, ethno-racial, gender, and class dimensions of its impacts.

Querétaro is a territory characterized by a colonial history of dispossession that continues to this day (Valverde, 2009; Valdovinos and Romero, 2025). The data center industry's impact in this state extends far beyond intensive water and energy consumption; it directly threatens the material and social subsistence of vulnerable, racialized populations. This crisis disproportionately affects women, who have traditionally spearheaded the defense of water, land, and territory. Furthermore, the industry jeopardizes the ancestral worldviews of Indigenous peoples, their forms of community governance, and the collective ownership of land and the commons.

To address the socio-environmental crisis in Querétaro, we propose a three-pronged analytical framework: (1) an eco-political approach, which recognizes the relational nature of data center infrastructure as the result of long-term historical, political, economic, and social processes across different scales, ranging from geopolitical forces to micropolitics; (2) a feminist and decolonial perspective, which sheds light on the dimensions of power and the differential impacts suffered by specific populations based on characteristics such as ethno-racial origin, socioeconomic status, educational level, and language, among others; and (3) A human rights and socio-environmental justice perspective, which respects the worldviews and self-determination of local peoples, and recognizes the right of both present and future generations to a dignified life and a healthy environment.

An eco-political, feminist, and decolonial perspective on data centers

In recent years, analyses of the socio-environmental impacts of data centers have focused primarily on water use, energy consumption, and carbon emissions (Gröger et al. 2025; Lehuedé, 2025; Siddik et al. 2021). We propose moving past the fragmentation of socio-environmental variables to examine the multidimensionality of the impacts on the affected territories. A socio-environmental approach cannot focus solely on intensive resource consumption, as this risks oversimplifying the complexity of the impacts.

En los últimos años, el análisis de los impactos socioambientales de la inteligencia artificial, y de los centros de datos en particular, se ha centrado principalmente en el consumo de agua, energía y emisiones de carbono. Aquí proponemos evitar la fragmentación de las variables socioambientales y abordar la multidimensionalidad de los impactos en los territorios situados. Un enfoque socioambiental no puede centrarse únicamente en el consumo intensivo de recursos, puesto que corre el riesgo de reducir la complejidad de los impactos.

Given that Mexico is a country marked by profound inequality, systemic violence, structural racism, and the enduring legacy of neoliberal policies, analyzing the data center industry's consequences for specific communities requires that we consider this historical, economic, political, sociocultural, and territorial context. This approach is vital if we are to recognize the industry as part of a historical continuum and its systemic nature of dispossession. Otherwise, a limited analysis of environmental impacts will inevitably lead to simplistic solutions typical of green capitalism or technosolutionist approaches, which ignore the real root causes and the lasting effects that the data center industry's expansion has on communities and territories.

Impact analysis must take into account the network of historical, political, geopolitical, economic, and sociocultural relationships that shape the territory. These relationships are marked by power imbalances, and have wide-ranging impacts on the local inhabitants, whose lives are adversely affected by the construction and operation of these infrastructures in the short, medium, and long term. An eco-political approach, therefore, is essential, as it frames the infrastructure within its broader socio-ecological context. This lens foregrounds the experiences of affected populations, reveals the historical dimensions of technological change, and exposes the political economies that determine what infrastructure is built, where, for whom, and at what cost. Crucially, this perspective also highlights the potential for grassroots and community resistance to achieve a sociopolitical and infrastructural reconfiguration of the territory. (Ricaurte, 2026)

Tracing Querétaro's history reveals that water has been at the center of power struggles within the territory since the colonial era. Five centuries later, history is repeating itself, with the underlying mechanisms of dispossession remaining largely unchanged. While narratives emphasize the scarcity of water—which is sacred in Indigenous cosmology—the local communities are not fooled: in fact, Querétaro's current ecological and social crisis is the direct result of a centuries-long process of mechanisms implemented to turn communal resources into private assets. This is why water, life, and territory defenders in Mexico articulate the root of the problem as follows: "It's not drought, it's plunder."

En este contexto, entendemos que el auge mundial de la industria de los centros de datos es una expresión material del capitalismo racial y de un orden colonial-patriarcal que privilegia los intereses del mercado en detrimento del bien social, buscando la acumulación capitalista mediante la desposesión. La industria de los centros de datos es una expresión de la colonialidad del poder a través de un modelo neoliberal de desarrollo tecnológico y una visión de sociedad que privilegia a élites locales y transnacionales –masculinas, heteropatriarcales y blancas– a costa de la destrucción de formas de vida de las comunidades feminizadas, racializadas y precarizadas. Por eso insistimos en que las resistencias a estas infraestructuras se encuentran enmarcadas en el contexto de las luchas históricas de las comunidades por la defensa de bienes comunes, el territorio y el agua, así como de formas comunitarias de vida y organización social que se remontan a la era colonial.

A decolonial and feminist approach, focused on human rights and socio-environmental justice, works by identifying two core structural realities. First, it highlights how capitalist, colonial, and patriarchal systems of violence perpetuate the historical continuum of dispossession, using various mechanisms—legal, institutional, infrastructural, discursive, sociocultural, and coercive—to accumulate wealth. Second, this approach emphasizes how the resulting impacts are shaped by gender, ethno-racial origin, class, and other forms of difference which directly limit access to specific rights. For Mexico, this means bringing the complex realities—of affected territories and social groups mobilizing against data centers—into focus within their broader, historical landscape of struggle.

Querétaro: the history of industrial development and the privatization of the commons

Querétaro, a small state in north-central Mexico (Figure 1), is defined by a geographically and ecologically diverse landscape that ranges from deserts to tropical rainforests. For nine thousand years, this part of the Great Valley of Mexico was home to Indigenous groups, including the Otomí, Purépecha, Chichimeca, and other nomadic and agricultural societies. These communities established themselves in regions suitable for farming, metalworking, textile production, and hunting, and their settlements were consistently located near dependable water sources.

After the colonial invasion, local populations had to choose between being subjugated or collaborating with the Spanish to secure political privileges. The latter strategy was adopted by certain Otomí lords who helped displace other groups into neighboring territories. Through a variety of means, colonizers gradually seized the best lands and water sources. Querétaro became a strategic location, positioned on the crucial trade route linking the silver mines of Zacatecas and Guanajuato to Mexico City.

Since the colonial era, different activities of production—initially agriculture, livestock, and the textile industry—have developed in the region. As economic activity grew, each industry demanded greater amounts of land, infrastructure, technology, labor, and water resources. Consequently, colonizers established institutions, laws, and infrastructure to enable the seizure and privatization of these vital goods.

The historical drive to privatize land, which began during the colonial era, was temporarily reversed by the 1910 Mexican Revolution and the agrarian reform enshrined in the 1917 Constitution. These reforms enabled a return to communal land ownership with protected access to water sources. However, as the 20th century progressed—particularly during Mexico's neoliberal era—this progress was undermined by efforts to remove all barriers to the free market, leading to the intensive privatization of the commons.

Following a long history of neoliberal governance, Querétaro has become an ideal site for business expansion and capital accumulation. Over the last two decades, the state has become a major hub for the automotive, aerospace, and electronics industries, focusing on the creation of industrial parks as spaces to facilitate growth. In recent years, the data center industry has emerged as a new focal point in the state government's narrative of entrepreneurial growth and industrial development (Valdivia, 2024; Bakarat e al., 2025). However, the rapid arrival of these centers has intensified pressure on ecosystems (Baptista and McDonnell, 2024) and exacerbated existing patterns of dispossession and inequality, particularly in relation to forms of communal land ownership (such as ejidosII), protected areas, water, and energy access.

Data center infrastructure embodies a clash between two fundamentally incompatible forces. On one side are the economic and political global forces behind a development model promoted by highly industrialized countries and endorsed by international organizations and local elites. On the other side are the community forces of the territory with their particular social and cultural differences that resist the dominant technological development paradigm and the global free-market system. In Mexico this resistance takes the form of communal land ownership, the governance of the commons, local social organizing, and life-sustaining practices deeply rooted in the territory.

Querétaro: "The valley of data centers"

Querétaro has firmly established itself as Mexico's leading data center hub, controlling 65% of the national capacity and attracting more than 80% of all current and planned investments for the years to come. With 27 data center projects (Figure 2), conservative estimates place the total investment at approximately $15 billion (Opportimes, 2025).

Querétaro currently has 18 operational data centers, with an estimated capacity exceeding 600 MW by 2025 (Baxtel, 2025). At least 13 of these are hyperscale facilities, operated by Amazon (AWS), Microsoft, Google, Oracle, Odata, Equinix (MX3), Digital Realty, CloudHQ, and Scala. These are in addition to traditional data centers managed by established firms such as IBM, KIO Networks, Axtel/Alestra, and Equinix (MX1/MX2). (Table 1)

| Company | Project/Location | Announced investment (USD) | Area (m²)(m²) | Capacity (MW) |

| ODATA | QR04 | 24 | ||

| ODATA | DC QR03 (campus) | $3,000,000,000 | 275,000 | 300 |

| ODATA | QR01 | $80,000,000 | 52,350 | 32 |

| ODATA | QR02 | 22,373 | ||

| CloudHQ | QRO Campus (Colón) | $3,400,000,000 | 253,068 | 288 |

| Digital Realty/Ascenty QRO1 | MEX01 | 20,000 | ||

| Digital Realty/Ascenty QRO2 | MEX02 | 23,969 | 31 | |

| Digital Realty/Ascenty QRO3 | MEX03 | 20,000 | 21 | |

| KIO Networks | QRO1 | 4,108 | 6 | |

| KIO Networks | QRO2 | 12,917 | 12 | |

| KIO Networks | QRO3 | $400,000,000 | 25,000 | |

| ORACLE | Mexico Central MX-Queretaro-1 | |||

| Equinix | MX1 – Querétaro | 10,000 | ||

| Equinix | MX2-Querétaro | 7,400 | ||

| Equinix | Mexico City 3x-1 | $140,000,000 | 4 | |

| AWS (Amazon Web Services) | Región AWS México (Central) – clúster en Querétaro | $5,000,000,000 | ||

| Microsoft (Azure) | Región México Central – área metropolitana de Querétaro | $1,100,000,000 | ||

| Google Cloud | Google Cloud Region en Querétaro | |||

| Total | USD 13,120,000,000 | 726185.36 | 694 |

Mexico is currently the third-largest data center market in Latin America after Brazil and Chile; however its rapid growth is quickly narrowing that gap (Mensky et al. 2024). In 2024, the country already accounted for approximately 2% of the global data center asset management market. The domestic market is forecast to reach $2.26 billion by 2030, with a compound annual growth rate of 13.5% (Expansión, 2025). The Mexican Data Center Association (Asociación Mexicana de Centros de Datos) estimates that the sector will contribute 5.2% of the national GDP, equivalent to $73.536 billion, by 2029 (Expansión, 2025).

Mechanisms of dispossession

The highway connecting Mexico City to Querétaro is a visual reminder of the relationship between industrialization and infrastructure: a relentless flow of huge trucks dominates the road, making it an intimidating route to travel. Long before reaching the city, the landscape is defined by spectacular billboards advertising real estate, land, and industrial warehouses. In this state, everything seems to be for sale.

The configuration of the territory stands at a critical turning point, in which the convergence of historical industrialization, demographic pressures, and new forms of capitalist accumulation within the technology sector have generated an unprecedented socio-environmental crisis. The expansion of data centers is not a new phenomenon, but rather the latest evolution of long-standing industrialization patterns endorsed by the state and sustained by neoliberal policies until the present day. Although this history can be traced back to the colonial era, the state also strengthened its commitment to foreign investment in the 19th century through the provision of industrial infrastructure and the systematic exploitation of local resources for external markets.

We argue that Querétaro's rapid transformation into a data center hub is the result of a long-term, systemic process of dispossession. This process is driven by various mechanisms that operate both actively and passively across multiple spheres: political-legal, institutional, economic-fiscal, discursive-narrative, infrastructural, and coercive. Specifically, this complex framework includes: neoliberal policies and laws facilitating privatization; promotion of foreign direct investment and tax exemptions; institutional compliance; the leveraging of public infrastructure; governmental and corporate opacity framed by a development narrative; and the use of force and police coercion.

In the following analysis, we will briefly detail some of these mechanisms of dispossession.

Neoliberal policies

Starting in 1982, the neoliberal policies advanced by the governments of Miguel de la Madrid and Carlos Salinas de Gortari created highly favorable conditions for the free market. The massive privatization of state-owned companies, financial deregulation, and the 1994 signing of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) all directed the Mexican economy toward export manufacturing and foreign direct investment. Querétaro successfully developed the automotive and aerospace clusters that prepared the region for the digital revolution. (Gobierno del Estado de Querétaro, 2023)

The aerospace sector, which has undergone intensive development since the start of the century, has been crucial to the emergence of today's data centers. With over 50 aerospace companies (including Bombardier, Safran, and Rolls-Royce) and $292.8 million in investment (2006–2024), the sector established specialized infrastructure, a highly skilled workforce, and regulatory frameworks that eased the subsequent transition to digital technologies. The technology sector is now capitalizing on state investments in technical training, such as the Aeronautical University of Querétaro (2007) and the National Center for Aeronautical Technologies (2018). Furthermore, the construction of the new airport facilitated connections with other markets. (García, 2024)

In this way, the rapid industrialization of recent decades created the infrastructural conditions necessary for Querétaro to emerge as a global data center hub. It has attracted approximately $12 billion in estimated investment (a conservative figure, given the lack of public disclosure) from multinationals like Microsoft, Amazon, and Google, as well as specialized operators (KIO Networks, Equinix, Ascenty/Digital Realty, ODATA) to establish what authorities call the "data center valley" or what Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella baptized as the "AI region." Yet this rapid influx of capital, framed by official narratives as simple economic growth (AM Querétaro, 2023), has triggered profound ecological, social, and political conflicts, exacerbating historical disputes over water, land, and territory.

Querétaro's emergence as a data center hub is the direct result of a deliberate strategy by the state government, led by Governor Mauricio Kuri (2021-2027, PAN). To attract foreign direct investment in the digital sector, the administration offers tax exemptions, fast-tracked permits, fast-tracked permits, co-investment in infrastructure, and the provision of land for industry (Caballero, 2024; Estrella, 2024). The governor famously boasted of having visited Washington, D.C. in his first week of term to convince tech companies to settle in the region, stating: "Mexico is the complement that American companies need for their development" (ReQronexión, 2021). At the same time, there has been significant public investment in the development of industrial parks and expansion of the electricity grid and water distribution systems to support the operation of these massive facilities (Diario de Querétaro, 2024; Opportimes, 2025).

As such, state policy actively enables the creation of data centers by offering simplified licensing procedures and comprehensive infrastructural support. The Secretaría de Desarrollo Sustentable, SEDESU (Secretariat of Sustainable Development), headed by Marco del Prete, serves as the main liaison between the government and business sector, managing both investments and environmental impact, thereby facilitating the company establishment process: "Querétaro is one of the few states nationwide that concentrates economic and environmental policies in a single agency" (Ocampo, 2025). This centralization allows SEDESU to set environmental compliance rules, effectively streamlining the processes for companies while simultaneously preventing adequate public accountability.

The current boost to the data center industry is a clear result of market-favorable neoliberal policies, effectively reproducing Mexico's historical subordination within the global economy. Integration into the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1994, and its successor The United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) in 2018, accelerated a manufacturing-oriented model that effectively turned the country into a product maquiladora. Today, the promotion of the data center industry follows this exact pattern, transforming us into infrastructure maquiladoresIII for the digital economy. This process involves storing foreign data on our territory at a high social and environmental cost; the data and artificial intelligence value chain therefore reinforces unequal power dynamics.

While data center infrastructure physically expands into new territories, the profits, governance, and knowledge remain concentrated among a few corporations, predominantly located in the United States. This is to say that the official narrative of Querétaro's "competitive advantage" in nearshoring ultimately serves to justify Mexico's subordinate position within digitized global value chains, replicating the dynamics of traditional extractivist schemes. (Brookings Institution, 2024; ECLAC, 2024)

Laws

Policies must go hand in hand with legal mechanisms, if they are to enable dispossession. Since the late 20th century, neoliberal governments in Mexico have systematically dismantled the state apparatus through the massive privatization of national companies and communal assets, including telecommunications, energy, oil, and water. These legislative reforms allowed for a significant concentration of capital among various national and foreign corporations.

With regard to water, two key pieces of legislation enabled privatization in Querétaro. First, the 1992 Ley de Aguas Nacionales (National Water Law) opened the door for individual and legal entities, private and public, to obtain concessions for the exploitation of water sources. Next, in 2022, the Querétaro State Congress approved the Law Regulating the Provision of Drinking Water, Sewerage and Sanitation Services in the State of Querétaro. This essentially privatized the operation of the service through concessions, construction contracts, or public-private partnerships, granting these operators the right to initiate water works and charge for usage (Ley de Aguas Nacionales, 1992; Ley Estatal del Agua, 2022). Activists and academics have widely noted that this law fails to align with national and international standards and does not take updated assessments of aquifer balance or watershed restoration into account. (Aristegui Noticias, 2022; Contralínea, 2024)

Regarding the energy sector, neoliberal reforms enacted in 1992, 2013, and 2014 opened up the market to private producers, creating an unequal competition with the Comisión Federal de Electricidad, CFE (Federal Electricity Commission) (Villegas, 2021). By 2024, the classification of "state-owned productive enterprises" was dismantled, and the CFE and Pemex were restored to their status as public entities, with plans to expand both national energy generation and transmission capabilities. (Gobierno de México, 2024; El Economista, 2025)

As far as land tenure, the 1992 reform of Article 27 terminated Mexico's post-revolutionary commitment to agrarian redistribution, thereby legalizing the privatization of ejido lands and dramatically reshaping the relationship between the state, the territory, and rural communities established in the 1917 Constitution. The subsequent 1992 Ley Agraria (Agrarian Law) established specific mechanisms that enabled this privatization: Article 56 granted ejido assemblies the power to determine land use and divide the land into parcels, while Articles 81 and 82 set the procedures for achieving "full ownership," which allowed ejido land to become private property. The law states that: "the federal and state governments shall encourage reconversion, in terms of a sustainable productive structure, incorporation of technological changes, and processes that contribute to the productivity and competitiveness of the agricultural sector, to food security and sovereignty, and to optimal use of land through complementary support and investment." (Ley Agraria, 1992)

The 2013 energy reform also resulted in a significant loss of communal land rights. By legally declaring oil, mining, and electricity to be sectors of national priority, the reform created pressure for ejido members to accept the Programa de Certificación de Derechos Ejidales, PROCEDE (Ejido Rights Certification Program). By granting individual property titles, PROCEDE enabled the sale or lease of parcels to private corporations (Vázquez-García and Sosa-Capistrán, 2021). This conversion of communal or ecologically protected lands into private property is best understood as a strategic process to prepare the earth for future capitalist accumulation.

Public infrastructure

Another mechanism of dispossession involves putting public infrastructure at the service of private corporate interests. Corporate expansion is directly enabled by this infrastructure through two means: first, by offering tax exemptions that reduce public revenue; and second, through direct public investment in energy, water, roads, and land access for industrial parks where data centers are built. This strategic scheme ensures that costs are socialized while profits and benefits remain privatized.

Sectoral projections anticipate accelerated growth in IT and AI investment between 2024 and 2028, with energy demand expected to quadruple (Calderón, 2024). To meet this demand, the state government has already announced unprecedented public investments in high-voltage lines and substations (Diario de Querétaro, 2024). At the federal level, the 2025–2030 Plan de Fortalecimiento y Expansión del Sistema Eléctrico Nacional (Plan to Strengthen and Expand the National Electricity System) confirms this trajectory, placing the CFE as the central player in upcoming generation and transmission projects. (El Economista, 2025)

Institutions

Subordinating public institutions to the interests of private companies serves as another mechanism enabling dispossession. The data center industry thrives because numerous government institutions facilitate its growth without establishing clear regulation, control, or public accountability. On the one hand, government bodies are instrumental in paving the way, providing everything from legal permits and tax agreements to guaranteed access to land, water, and electricity. One prominent actor here—besides the Governor—is the head of SEDESU, who has repeatedly downplayed the socio-environmental impacts of this emerging industry and has not made public the environmental impact assessments. On the other hand, the Comisión Nacional del Agua, CONAGUA (National Water Commission), which is tasked with allocating water use concessions and setting consumption limits, obstructs public access to information regarding the industry's specific water consumption. The Comisión Federal de Electricidad, CFE (Federal Electricity Commission), responsible for the electricity grid infrastructure, establishes operational conditions and usage parameters at a federal level, including setting the consumption capacity that industrial parks must have. Regarding land, the Secretaría de la Reforma Agraria (Secretariat of Agrarian Reform) and the Registro Agrario Nacional (National Agrarian Registry) are the federal entities tasked with overseeing and registering land conversion processes.

Discursive narratives

SEDESU head Marco Antonio del Prete asserts that "Querétaro is establishing itself as a hub for data cloud development thanks to its strategic location, security, and respect for investment" (Estrella, 2024). This official narrative presents Querétaro as the most desirable state for foreign direct investment. Operating from a neoliberal perspective, the administration of Governor Mauricio Kuri (of the PAN political party) has actively created the necessary legal, institutional, and infrastructural conditions to prioritize the business sector, treating foreign direct investment as the primary indicator of government success. (Reynoso, 2025)

Under this scheme, recent years have been marked by the creation of narratives designed to promote economic development, as driven by investment and infrastructure growth. As previously noted, while the exact figure remains undisclosed—with some sums kept confidential—the total investment in the data center industry is conservatively estimated at $15 billion.

Within this context, the arrival of major technology corporations has been enthusiastically welcomed. The presence of these companies—particularly those operating hyperscale data centers[2] — has materialized in Querétaro over the last three years. In 2022, Oracle began installing its hyperscale centers, with other companies following suit. In 2024, Microsoft launched its "Central Mexico" region, and Google inaugurated its cloud region in late 2024.

AWS also announced a multi-year investment plan involving the creation of three availability zones (Microsoft News Center, 2024; DCD, 2024; El Financiero, 2025). Meanwhile, specialized operators like ODATA and CloudHQ further consolidated their presence in the state (AP, 2025; ODATA Colocation, 2025a, 2025b). According to ODATA, the data center inaugurated in early 2025 is the largest in all of Mexico.

Despite the triumphant narratives, the unfolding of the data center industry in Querétaro is fundamentally characterized by corporate opacity orchestrated alongside government secrecy, casting significant doubt on any claims that it will benefit society. There is no comprehensive public record detailing the number, capacity, licenses, environmental impact assessments, or energy and water consumption of these facilities. Additionally, government agreements regarding tax exemptions, land transfers, and even the actual number of "supposed" jobs generated by this industry are hidden from public scrutiny. Projections regarding job creation are often accompanied by grandiloquent estimates of economic benefits that currently lack empirical evidence to support them. Unfortunately, this failure in transparency is part of a global pattern.

While Querétaro's documented centers belong to leading regional, national, and global players, the hyperscale facilities are not necessarily publicly registered. In Google's case, the company has withheld all information about the investment, location, and nature of its hyperscale center, citing "competitive reason" as the justification. Consequently, initiatives designed to document these infrastructures globally, such as the Data Center Map, rely on voluntary contributions and are often incomplete or outdated.

Accumulation through dispossession

The data center industry represents the latest link in the chain of industrialization processes that have led to the current socio-environmental crisis. In this section, we show how the industry affects local communities through the appropriation of common resources: water, energy, air, and land.

Water

"We are facing a severe drought in the city of Querétaro. It is one of the first cities predicted to run out of water," states Teresa Roldán, co-founder of the Voceras de la Madre Tierra, when discussing the state's environmental crisis. Teresa, a tireless advocate for the environment and life, adds: "Since 2016, I have defended the trees, the protected natural areas, and everything in the park area—what was supposed to be the Metropolitan Park." This project was abandoned after a massive real estate boom that reclassified protected land for the purpose of developing housing.

In April 2025, the CONAGUA Drought Monitor indicated that 95% of the state's territory was affected by critical water shortages (La Voz de Querétaro, 2025). This water crisis is pushing the state toward the brink of environmental and social collapse. Prior to the colonial invasion, the territory now occupied by Querétaro was rich in rivers and springs. Since colonization, however, land and water have been subject to dispute. Decisions regarding access to land and water have consistently favored elite groups and industrial interests at the expense of local communities, who have been displaced and stripped of their territories and water sources. (Valverde, 2009)

Querétaro's aqueduct was built to transport water from the Capulín spring in San Pedro de la Cañada to the city fountains, which supplied religious institutions and privileged groups in the city (Valdovinos and Romero, 2025). Celebrated as an impressive feat of engineering, the aqueduct actually served a hidden purpose: to conceal the pollution of the Río Blanco (now the Querétaro River) caused by industrial waste. Consequently, while the city's elites were supplied with clean water, Indigenous communities surrounding the Cañada spring were left with a polluted supply. This logic closely resembles that of the proposed El Batán project, where the government plans to use treated water for human consumption while clean water goes to the data centers.

Querétaro faces a deep history of water dispossession through accumulation, stemming from the imposition of an extractivist paradigm that has been intensified by industrialization and regional integration in North America since the 1990s (Jacobo-Marín, 2024). The report Los millonarios del agua (The Water Millionaires) reveals that, since the 1992 Water Law, approximately 7% of concessions utilize 70% of the local water volume (Gómez-Arias and Moctezuma, 2020). In Querétaro, a small group of state concessionaires monopolize over 50 million m³ of water annually, while more than 100,000 homes lack access to running water. (INEGI, 2023; Saavedra Rivera and Martínez Ramos, 2024)

Quantifying the water consumption of these data centers is difficult, primarily due to corporate opacity. Moreover, obtaining accurate measurements poses methodological challenges for the public, as both direct consumption (used in cooling systems) and indirect consumption (associated with the generation of electricity required for their operation) must be considered. In a context of severe water stress such as Querétaro, each unit of water extracted has a far greater impact than it would in a less water-stressed region.

Although some companies, such as ODATA, claim to use air cooling systems instead, or "water positive" strategies (BNAmericas, 2025), they consistently fail to publish their Water Use Efficiency (WUE) data. Independent verification also remains limited. The state government is another obstacle to assessing water consumption, as it promotes the installation of centers in industrial parks. Since water management is handled through the transfer of CONAGUA concessions and allocations within these parks, the total volume of resources committed to the industry is effectively concealed. Authorities actively reject requests to disclose the volumes assigned to each company, thereby fueling public mistrust.

We must take seriously the lesson learned from the Querétaro case. Mexico is currently experiencing one of the most widespread and intense droughts in recent decades. According to CONAGUA, in 2023, approximately 80% of Mexican territory faced drought conditions (Figure 4). The water crisis unfolding in Querétaro foreshadows what lies ahead for the country. Mexico is projected to become one of the countries facing the highest water stress on the planet. (World Resources Institute, 2023)

Energy

The data center power demand is critical and is directly tied to the issue of indirect water consumption. Querétaro is already struggling with a structural energy deficit and a growth in demand that exceeds the national average, with the industrial sector consuming roughly 70% of the installed capacity (Gobierno del Estado de Querétaro, 2023). Data from México Evalúa (2024) shows that electricity consumption in the state increased from 4,923,884 MWh in 2015 to 5,039,836 MWh in 2022, alongside a 33.59% increase in the total number of users. This growth in pre-existing demand, combined with the enormous requirements of the new data centers, forces us to question the viability of the state's electricity system. (Figure 5)

Querétaro's installed/projected energy capacity is estimated at 690 MW, yet projections suggest that an additional 1,490 MW will be needed in the coming years. This critical deficit is compounded by the fact that, at the national level, Mexico relies heavily on fossil fuels, which account for nearly 80% of the primary energy supply. (GEM, 2024; Ministry of Energy, 2024)

According to the Asociación Mexicana de Centros de Datos, ASOMEXDC (Mexican Data Center Association), while "Mexico has good connectivity that allows for minimal latency," the country requires several conditions for growth, including "more specialized labor, competitive costs for both energy and renewable sources, and a transparent, simple, and stable regulatory framework, as well as the availability of more industrial land with energy access," which ultimately translated into state policy. (https://asmexdc.com/la-asociacion/)

Reports of power outages in several Querétaro neighborhoods have become common (González, 2025). This unreliability reflects a growing structural problem, with a 151% increase in outages between 2014 and 2023 (Santoyo, 2023). Combined with the water crisis, these failures underscore the fragility of the state's electrical system. This situation raises serious doubts about priorities in the distribution of energy resources and the state's commitment to equity regarding access to basic services.

While a stable energy supply is guaranteed for corporate activities, neighboring communities frequently face interruptions and shortages in the electricity supply (Diario de Querétaro, 2024). Furthermore, promises to power data centers with renewable energy require rigorous scrutiny in order to avoid greenwashing and to assess the territorial and social impacts associated with the generation and transmission projects which are needed to supply these facilities.

Air

Data centers are confirmed contributors to CO2 emissions and air pollution due to their reliance on fossil fuels and their energy consumption. Furthermore, the diesel backup generators used by these facilities emit fine PM2.5 particles and nitrogen oxides (NOx). These substances are proven to have adverse effects on human health, especially in the suburban and urban areas where data centers are typically located. (Gradient Corporation, 2024)

The forecast regarding these impacts is far from encouraging. Globally, data centers currently consume an estimated 415 TWh, but projections suggest this figure could double by 2030 (IEA, 2025), potentially surpassing even the most polluting traditional industries. In the face of the rapid growth of AI, energy demand will increase and, with it, the emissions associated with AI's development, implementation, and everyday use. (RMI, 2024)

Although there are no specific local studies quantifying PM2.5 and NOx emissions from Querétaro data centers, international reports confirm that backup generator emissions pose a significant risk to air quality and human health. It is therefore plausible that the periodic operation of these generators contributes a considerable pollution load to the area. Concerns have already been raised regarding the environmental consequences and health risks of using highly polluting power plants to generate electricity in the Valley of Mexico. (Energía a Debate, 2017a, 2017b)

Although there are five air quality monitors in the Querétaro Metropolitan Area and one in San Juan del Río (https://aire.cemcaq.mx), these do not cover all the areas where data centers are currently located. A lack of regulatory oversight (Juárez, 2024)—combined with the absence of differentiated treatment of data centers as an industry—effectively serves to reinforce the invisibility of the issue.

Land

The expansion of industrial parks and data center campuses in Querétaro is encroaching on water recharge zones and areas set aside for ecological conservation or community use. This process repurposes land for industry and fragments local ecosystems, threatening not only biodiversity but also traditional communal ways of life and land governance systems. As a result of the 1910 Revolution, Mexico has maintained a unique land structure: over half of its territory is socially owned — organized into ejidos and agrarian communities—providing a legal framework for collective management of resources. However, constitutional reforms in 1992 enabled privatization, driving corporate and government interest in this land for industrial use. This neoliberal policy—promoting territorial transformation to the detriment of local communities and the benefit of industry and real estate—is one of the causes of the state's ecological crisis.

Querétaro contains over 360 ejidos, which account for approximately 55% of its cultivated land (Código Informativo, 2020). However, the 1992 constitutional reforms that permitted the privatization of ejidos created significant structural vulnerabilities to land grabbing. Journalistic investigations have since documented the existence of an “agrarian mafia” that exploits these legal loopholes to appropriate communal lands through document falsification and notarial corruption. (InformativoQ, 2021)

The town of Cerro Prieto in the municipality of El Marqués serves as a clear example: the community's land was expropriated through questionable legal proceedings that fabricated false communal landowners to justify the sale (EJAtlas, 2022). Almost immediately after the fraudulent transfer, wells were drilled and infrastructure—including pipelines—was installed to support future residential and industrial projects. Activists who opposed the land expropriation and water diversion have been criminalized, arrested, and tortured under false accusations of land invasion and public disturbance.

As previously mentioned, the Mauricio Kuri administration employs various legal mechanisms to facilitate corporate access to the territory. Trusts, for example, allow companies to acquire land in exchange for investment commitments. Meanwhile, utilizing existing infrastructure within industrial parks—which comes with pre-approved zoning and environmental permits—effectively streamlines the process of setting up new data centers.

Currently, the area occupied by data centers is estimated at 975,079 m² (derived from properties with publicly available size data). Moreover, up to 300 hectares have been officially authorized for new industrial parks in strategically located municipalities such as El Marqués, Colón, and San Juan del Río (Galván, 2024). (Figure 6)

It is possible to document the processes of land-use conversion for data center construction in only a few cases. In most instances, these processes remain invisible, either concealed by "corporate secrecy" or obscured by the succession of different stages in the conversion process. However, the organization Micelio Urbano has documented the systematic replacement of milpas (traditional, pre-Hispanic crops) with data center infrastructure, which effectively reorganizes socio-ecological environments to meet the needs of capital accumulation. (Ecoosfera, 2024)

In the case of CloudHQ, the state government approved a trust that contributed 518,470 m² of land—valued at approximately 17.7 million USD—for a 288 MW campus involving a $4.8 billion investment (AP, 2025; Butler, 2023). The Digital Realty MEX03 case provides the clearest evidence linking a data center to a specific ejido parcel: "Parcel 10 Z-1 P1/1 of the San Vicente Ejido." Under Mexican law, this would have required assembly minutes authorizing the subdivision and, if applicable, the shift to full ownership (dominio pleno), followed by registration in the National Agrarian Registry before the land was transferred.

Data regarding the exact land tenure of the Microsoft, Amazon, and Google data center sites is currently unavailable. However, it is possible to conduct an initial exercise to identify evidence of the repurposing of communal lands within the industrial parks where these clusters are situated. Table 2 presents the public instruments revealing which ejido units are involved in the areas where data centers are concentrated in Colón, Querétaro, and whether there are indications of the adoption of dominio pleno. This legal mechanism allows an ejido parcel — originally belonging to the collective ejido — to become the private property of the individual ejido member. Once converted, the parcel leaves the agrarian system and becomes subject to civil law, enabling it to be sold, leased, mortgaged, subdivided, inherited, incorporated into a company, or used as collateral (Ley Agraria, 1992, Articles 81–83). Given that this mechanism has allowed communal land to be converted into private property, we can track the granting of dominio pleno as an indicator of the privatization of land for the data center industry. We present this systematization as a preliminary step in this line of analysis; however, future studies will require multiple public information requests to trace the full trajectory of communal land privatization.

| Comunal land unit / parcel | Legal document (type) | Date | What the legal document asserts | Link to data centers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Purísima de Cubos Ejido – Parcel 59 Z-1 P1/1 (Land register code 05 04 061 66 410 059) | Gaceta MunicipalIV de Colón, Number 66, Tome I (Municipal Council Agreement: division into parcels/ Novotech Airport expansion; EIAV and previous approvals) | September 17th, 2024 | Exact location (Road to San Vicente 949), surface area, permit history record (2017-2024), incorporation of industrial parceling | Industrial park where parcels for data centers were developed/marketed near Querétaro International Airport. |

| Purísima de Cubos Ejido – Parcel 63 Z-1 P1/1 (Land register code 05 04 06 166 410 063) | Gaceta Municipal de Colón, Number 66, Tome I (authorization to expand – Stage II Novotech Airport) | September 17th, 2024 | It includes 77,836.55 m²; details the usage percentages (industrial, roads, etc.) | Same area as the data center cluster. |

| Purísima de Cubos Ejido – Parcel 59 Z-1 P1/1 | Acta del AyuntamientoVI (ordinary session) preceding Gaceta 66 | August 27th, 2024 | Reasserts MIAVII (SEDESU/132/2018), EIU/EIVVIII 2018, self-sufficient water supply, "light industry" use | Prior administrative basis. |

| Purísima de Cubos Ejido – Parcel 59 Z-1 P1/1 | Gaceta Municipal de Colón, Number 43, Tome I (records) | July 21st, 2020 | Total area 77,874.054 m²; CFE electrical feasibility; self-sufficient water supply, etc. | Record of the industrial project that enables the arrival of data centers. |

| San Vicente Ejido – Parcel 10 Z-1 P1/1 | Ficha oficial del emplazamientoIX MEX03 (Digital Realty) | n/d (in force) | The corporate address is recorded as: Parcel 10 Z-1 P1/1, San Vicente Ejido, Colón, 76295. | Link an operational data center to a specific communal land parcel. |

| Land units in Colón: Purísima de Cubos, Noria de Cubos, San Vicente El Alto | National Agrarian Registry [Registro Agrario Nacional, RANX] – Land units converting to full ownership (disaggregated) | Valid document | List of Querétaro Land Units converting to full ownership (basis for locating records and sheets in the RAN) | Evidence of full ownership conversion where industrial parks and centers are located. |

| State location of publications | Official Journal La Sombra de Arteaga, 2025 Index | 2025 | References to published agreements involving parcels 59 and 63 of Purísima de Cubos Ejido ((basis for locating records and sheets in the RAN) | Agreement traceability in the state official journal. |

The historical defense of water, life, and territory

The struggles for water, life, and territory in Mexico reveal a long history of resistance against policies of dispossession and the privatization of the commons. This resistance is expressed through active defense of the right to a dignified life, and is sustained by community practices rooted in principles of care, reciprocity, and collective organization.

In response to the systematic dispossession and devastation of their territories, water resources, and ways of life, various communities across the country have launched local and regional organizing efforts. These efforts are varied, ranging from legal defense and community organizing to the re-establishment of ancestral water management practices. Collectively, they constitute a powerful, organized resistance to the extractivist paradigm imposed by both private and state interests. Fundamentally, these initiatives aim to promote autonomous and sustainable alternatives that challenge the logic of commodification, reclaiming the sacred and communal nature of water and territory. (Moctezuma, 2020)

Different forms of political articulation within the Indigenous and campesino movement highlight persistent resistance over time, even in the face of systematic violence and dispossession. For example, the Congreso Nacional Indígena, CNI (National Indigenous Congress), which represents 523 communities belonging to 43 Indigenous peoples across 25 states, works to coordinate territorial defense against megaprojects and extractive industries (CNI, 2017). Since 2022, the CNI has also organized the Asamblea por el Agua y la Vida (Assembly for Water and Life), which unites different movements in the defense of water, life, and territory. (Figure 7)

Another key initiative is the Coordinadora Nacional Agua para Todos, Agua para la Vida (National Coordinator Water for All, Water for Life), launched in 2012 by researchers, collectives, and activists. This initiative connects local grassroots struggles, against privatization and water pollution, with Indigenous peoples and urban popular movements which are fighting for access to water resources and local control. This National Coordinator drafted and promoted a Citizens' Initiative for a General Water Law, which directly challenges the current neoliberal legal framework. This comprehensive proposal integrates principles of democratic management, distributive justice, community and domestic use prioritization, watershed and ecosystem protection, and mechanisms for social control and decentralization. By asserting water's status as a human right and common good, the initiative provides alternatives to opaque, centralized resource management and challenges corporate and state interests which are profiting from the status quo. (Moctezuma, 2020)

Indigenous groups, campesinos, collectives, and civil society organizations in Querétaro have undertaken numerous acts of resistance against the dispossession of water and territory. It is worth noting that the current opposition to data centers forms part of this broader, historical struggle; it is thus inappropriate to frame it as a resistance directed solely or exclusively against these infrastructures. The historical depth of this resistance in the territory is best exemplified by the struggle of the Otomí people, who were inhabitants of the region long before the arrival of colonizers and played a key role in the formation of present-day Querétaro.

The Otomí people's ongoing fight to regain their water and land took on new relevance when the LX Legislatura de QuerétaroXI approved the State Water Law on May 24, 2022. This law, which granted water supply concessions to private companies for up to 40 years—a veiled form of privatization (Torres-Mazuera, 2023; Bernal, 2024)—was met with immediate community resistance. Through organized demonstrations and forums, the community called attention to the fact that while urban developments and corporations did not experience water cuts, working-class neighborhoods and the Otomí community faced shortages, repression, and unfair prices (Pie de Página, 2022). On August 1, 2022, a federal court granted an injunction (907/2022), finding that the Ley de Aguas violated the Indigenous rights recognized by the Constitution (Articles 1, 2, 27) and by international treaties, especially since it had not been submitted for consultation with the affected communities. Despite this legal victory, CONAGUA and CEAXII have been reluctant to comply with the court-ordered restitutions. (Vázquez Cabal, 2024)

One of the most visible and active of the aforementioned organizations is Voceras de la Madre Tierra, which promotes the protection of natural recharge areas, challenges illegal land expropriations, and documents environmental degradation through social media, direct action, and formal legal complaints. Roldán and her fellow activists, however, have been excluded from public meetings where critical infrastructure decisions are made and, in some cases, forcibly removed from public spaces—despite legal provisions guaranteeing citizen participation in environmental governance.

Those involved in the movement have endured constant attacks, both verbal and physical. Roldán has been assaulted, and community allies in Escolásticas (a town in Pedro Escobedo municipality) have been arbitrarily detained and tortured. During a 2023 protest against the so-called Ley de Concesiones de Agua (Water Concessions Law), eleven protesters were detained and beaten, with one young man sustaining injuries so severe he was nearly paralyzed. Even after Roldán addressed the Supreme Court of Justice at a forum on the Escazú Agreement—an international treaty guaranteeing environmental defenders the right to participate in environmental decision-making—the government response has largely been one of silence. Although formal complaints were submitted and state authorities officially accepted public policy recommendations from the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights acknowledging these violations, no federal or state institution has provided a meaningful response to Voceras' demands to date. The actions of Voceras de la Madre Tierra articulate demands for human rights (access to water), government transparency, rigorous corporate regulation, and the recognition of Indigenous territorial sovereignty. Their successful intervention before the Supreme Court in July 2024 established a legal precedent for the judicial handling of hydrological-technological conflicts in Mexico.

However, the systematic acts of aggression and coercion against movements defending water, life, and territory—as well as against environmental organizations—clearly demonstrate that economic and political elites are not inclined to easily give up their misappropriation of land and water. These attacks also intersect with race, gender, and social status. Those who tend to stand on the front line of defense are predominantly women, and in community contexts, they are often members of Indigenous or campesino groups who lack resources and access to basic rights.

Notwithstanding, social organization remains the only viable mechanism for denouncing the systematic dispossession faced by communities and by inhabitants of territories that historically have been plundered since colonial times—today also subjected to the logic of digital plunder.

Conclusión

The Querétaro case demonstrates that data centers, often framed as indicators of digitization, modernization, and economic development, are deeply intertwined with histories of territorial dispossession, environmental degradation, and state-capital collusion. Their physical presence not only reconfigures territorial and social landscapes but also concentrates material and informational power, reinforcing colonial and capitalist modes of accumulation. The resulting socio-environmental impacts, borne disproportionately by historically marginalized communities, expose the profoundly unequal logic underpinning data infrastructure.

The ecological-political approach allows us to examine infrastructures within their broader socio-ecological contexts. It focuses on the embodied experiences of affected populations, the multiple impacts of technological development, and the political economies that determine what infrastructure is built, where, for whom, and at what cost. This perspective demands that we pay analytical and political attention to the values embedded in the project—its development, operation, and governance—and to the possibilities for grassroots resistance, along with socio-political and infrastructural reconfiguration.

As the civilizational crisis deepens, marked by the growth of the digital economy and the strengthening of authoritarian regimes, it becomes increasingly urgent to question how infrastructures mediate social relations, thereby shaping the material and immaterial conditions necessary to sustain life. Reimagining ecological-political infrastructures involves broadening practices of care, justice, and sustainability that are already creating alternative infrastructures for survival. Fundamentally, this process demands that we recognize communities not as passive recipients of infrastructural change, but as active agents in building dignified infrastructural futures.

Notes

1 ^ Existing figures on the sector are highly dynamic, involve numerous variables, and are often inconsistent or unavailable. The aggregate totals for investment (immediate, short, medium, or long term), occupied area (total and technical), and capacity in MW (initial and final) are calculated from publicly available information in various media reports. However, due to inconsistencies in the source data, estimates may vary. The figures presented should therefore be treated as illustrative references. The primary reason for missing data is the companies' policy of non-disclosure.

2 ^ A hyperscale data center is a large-scale facility designed to house more than 5,000 servers across an area exceeding 930 m² (approximately 10,000 ft²). These infrastructures require immense power capacity (100 MW or more) and are built with a modular, scalable architecture designed to expand easily and meet rising demand. To ensure maximum operational continuity and reliability, hyperscale centers incorporate high levels of redundancy and critical automation, delivering high levels of efficiency and technological integration across computing, networking, and storage systems.

References

- AM Querétaro. (2023, 14 de marzo). Querétaro, el valle de los «data centers» . AM Querétaro.

- A.P. (2025, Septiembre 25). CloudHQ invertirá 4.800 millones de dólares para el desarrollo de centros de datos en México .

- Aristegui Noticias. (2022). Policía agrede a manifestantes que exigen sepultar ley que privatiza el agua . Aristegui Noticias.

- Baptista, D. y McDonell, F. (2024). Thirsty data centres spring up in waterpoor Mexican town . The Context.

- Baxtel (2025). Mercado de centros de datos en Querétaro .

- Bernal, N. (2024). Las guardianas del agua en Santiago Mexquititlán . Ojalá.

- BNAmericas (2025). ODATA se expande en México con el lanzamiento de un centro de datos a hiperescala .

- Brookings Institution. (2024). USMCA y nearshoring: los desencadenantes de la dinámica comercial y de inversión en América del Norte .

- Butler, G. (2023). El estado mexicano de Querétaro aprueba un fideicomiso para el centro de datos CloudHQ de 4000 millones .

- Caballero, L. (2024). Querétaro impulsará entre 10 y 12 nuevos centros de datos . Quadratin Querétaro.

- Calderón, M. (2024). Mercado de Data Centers en México 2023–2027 . Mexico Business News.

- CEPAL. (2024). Perspectivas del Comercio Internacional de América Latina y el Caribe 2024 . Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe.

- CFE. (2024). Informe de la gestión gubernamental 2018–2024 . Comisión Federal de Electricidad.

- CNI (2017). Qué es el CNI .

- CNI (2024). Declaración de la 5a Asamblea Nacional por el agua, la vida y el territorio .

- Código Informativo (2020). 360 ejidos de Querétaro apoyados por el Gobierno de México .

- CONAGUA. (2023a). Estadísticas del agua en México 2023 . Comisión Nacional del Agua.

- CONAGUA. (2023b). Registro Público de Derechos de Agua (REPDA) . Comisión Nacional del Agua.

- Contralínea. (2024). Inician privatización del agua en Querétaro . Contralínea.

- DCD. (2024). El estado mexicano de Querétaro aprueba un fideicomiso para el centro de datos CloudHQ de 4000 millones de dólares . DataCenterDynamics.

- DCD. (2025, 5 de mayo). ODATA inaugura centro de datos en Querétaro . DataCenterDynamics.

- Diario de Querétaro. (2024). CFE invertirá 600 mdp en infraestructura eléctrica . Diario de Querétaro.

- Ecoosfera. (2024). Querétaro: Inversiones tecnológicas provocarían sequía y contaminación .

- EJAtlas (2022). Despojo por posesión ilegal de tierras en Cerro Prieto, Querétaro, México .

- El Economista. (2025, 5 de julio). Sheinbaum se compromete a construir 60 centrales de ciclo combinado de CFE . El Economista.

- El Financiero. (2025, 14 de enero). «Llegamos a México para quedarnos»: ¿De cuánto es la inversión de Amazon y cuántos empleos creará? . El Financiero.

- Energía a Debate (2017a, 20 de abril). Plantas energéticas de Tula, las más contaminantes: OCCA .

- Energía a Debate (2017b, 12 de septiembre). Termoeléctrica de Tula causa muertes prematuras: expertos .

- Estrella, V. (2025). Querétaro apuesta por la formación de talento para centros de datos . El Economista.

- Expansión. (2025, 27 de marzo). México ya es líder regional en data centers y en 2029 aportarán 5.2% al PIB .

- Galván, C. (2024). Hay 300 hectáreas autorizadas para nuevos parques industriales en Querétaro: SEDESU .

- García, M.L. (2024). Aeropuerto internacional de Querétaro, 1990-2023: de las ganancias millonarias y los pueblos olvidados . Tesis Doctoral. El Colegio de San Luis.

- GEM. (2025). Perfil Energético México . Global Energy Monitor.

- Gobierno de México. Presidenta Claudia Sheinbaum firma decreto que devuelve CFE y Pemex al pueblo de México como empresas públicas del Estado . Gobierno de México.

- Gobierno del Estado de Querétaro. (2023). Querétaro Competitivo. Anuario Económico 2023 .

- Gómez-Arias, W. A. y Moctezuma, A. (2020). Los millonarios del agua: Una aproximación al acaparamiento del agua en México . Argumentos. Estudios críticos de la sociedad, 17–38.

- González, C. (2025). Múltiples colonias de Querétaro y Corregidora llevan más de dos días sin agua y luz; conoce cuáles son . Al Diálogo.

- Gradient Corporation. (2024). Data center environmental and health externalities .

- Gröger, J., Behrens, F., Gailhofer, P., Hilbert, I. (2025). Impactos medioambientales de la inteligencia artificial . Greenpeace.

- IEA. (2025). Energy demand from AI . International Energy Agency.

- INEGI. (2023). Marco Geoestadístico, diciembre 2023 . Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía.

- INEGI. (2024). Estadísticas a propósito del Día Mundial del Agua . Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía.

- InformativoQ. (2021). Los dueños de Querétaro: los desarrolladores inmobiliarios .

- Jacobo-Marín, D. (2024). Despojo hídrico por acumulación: el caso de la minería metálica en México . Revista de la Facultad de Derecho de México, 74(288), 303–330.

- Juárez, U. (2024). Tribunal ordena a Profepa y Semarnat verificar que la termoeléctrica de Tula cumpla regulación ambiental .

- Lehuedé, S. (2025). Una ética elemental para la inteligencia artificial: el agua como resistencia dentro de la cadena de valor de la IA . AI and Soc 40:1761–1774.

- La Voz de Querétaro (15 de mayo de 2025). Sequía en Querétaro pone en riesgo abasto de agua .

- Ley Agraria. (1992, 26 de febrero). Ley Agraria .

- Ley de Aguas Nacionales. (1992, 1 de diciembre). Ley de Aguas Nacionales .

- Ley que regula la prestación de los servicios de agua potable, alcantarillado y saneamiento del Estado de Querétaro. (2022, 21 de mayo). Ley que regula la prestación de los servicios de agua potable, alcantarillado y saneamiento del Estado de Querétaro .

- Lugones, M. (2010). Toward a Decolonial Feminism . Hypatia, 25(4), 742–759.

- Mensky, M., Johnson, J. y de Feydeau, A. (2024). El auge de los centros de datos en América Latina exige acelerar la inversión en infraestructura . Enfoque sobre América Latina 2024. White and Case.

- México Evalúa. (2024). Perspectiva de la transición energética de Querétaro .

- México Now (2023). Data Centers to be Installed in Queretaro by 2024 .

- Microsoft News Center. (2024). Microsoft cumple 35 años transformando a México . Microsoft.

- Ministerio de Energía (México). (1 de octubre de 2024). Distribución del suministro de energía primaria en México en 2023, por fuente . Statista.

- Moctezuma, P. (2020). La iniciativa ciudadana de Ley General de Aguas: Hacia un cambio de paradigma . Argumentos Estudios críticos de la sociedad, 109–130.

- Ocampo, I. (2025). Liderazgo en desarrollo económico sostenible . Alcaldes de México.

- ODATA Colocation. (2025a, 27 de febrero). ODATA anuncia la energización del campus de centros de datos más grande de México .

- ODATA Colocation. (2025b, 1 de mayo). ODATA anuncia el lanzamiento de su mayor centro de datos en México (300 MW) .

- Opportimes. (2025). Los 12 centros de datos en Querétaro: 15,000 millones de dólares en inversiones .

- Pie de Página (2022). Habitantes de Santiago Mexquititlán demandan a Conagua el control de su pozo .

- Research and Markets. (2025). Informe sobre el panorama del mercado de centros de datos en América Latina 2024-2029 .

- ReQronexión. (2021). Querétaro es el complemento que necesitan las empresas americanas para su desarrollo .

- Reynoso, J. (2025). Querétaro entre los 5 estados con más anuncios de inversiones en 2025 .

- Ricaurte, P. (2026). Sobre la ecopolítica de los centros de datos: una investigación feminista descolonial. Ciencia, tecnología y valores humanos. De próxima publicación.

- RMI. (2024). Impulsando el auge de los centros de datos con soluciones bajas en carbono . Rocky Mountain Institute.

- Robinson, C. J. (2020). Black Marxism: The making of the black radical tradition. UNC Press Books.

- Saavedra Rivera, M. L., & Martínez Ramos, S. A. (2024). Visualizando datos: Estudio exploratorio sobre los riesgos de la escasez del agua en el Estado de Querétaro . Economía Creativa, (21), 154–171.

- Santoyo, C. (2023). Querétaro a oscuras: Crecen 151% las fallas de energía de la CFE . Tribuna de Querétaro.

- Siddik, M. A. B., Shehabi, A., Marston, L. (2021). La huella medioambiental de los centros de datos en Estados Unidos . Environmental Research Letters, 16(6), 064017.

- Valdovinos, J., & Romero, C. (2025). Los acueductos de Querétaro, México: patrimonio cultural del agua que normaliza la escasez provocada . Agua y Territorio/Water and Landscape, (25), 267–281.

- The Maybe. (2025). Cuando las nubes se encuentran con el cemento. Análisis de un caso práctico sobre el desarrollo de centros de datos .

- Torres-Mazuera, G. (2023). Privatización, acaparamiento y mercantilización de la propiedad social. Saldos neoliberales de la reforma al Artículo 27 constitucional de 1992 . CCMSS.

- Valdivia, A. (2024). El capitalismo de la cadena de suministro de la IA: un llamamiento a (re)pensar los daños algorítmicos y la resistencia a través de la lente medioambiental . Información, Comunicación y Sociedad, 1–17.

- Valverde, A. (2009). Santiago Mexquititlán: un pueblo de indios, siglos XVI–XVIII . Dimensión Antropológica, 16(45), 7–44.

- Vázquez Cabal, L.A. (2024). Agua, comunidad y conflictividad social en Santiago Mexquititlán . Tesis de Maestría. Universidad Autónoma de Querétaro.

- Vázquez-García, V., & Sosa-Capistrán, D. (2021). Examining the Gender Dynamics of Green Grabbing and Ejido Privatization in Zacatecas, Mexico . Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 5.

- Villegas, C. (2021, 11 de marzo). La ruta de la privatización de la electricidad . Proceso.

- World Resources Institute. (2023). Aqueduct Water Risk Atlas .

Translator's Note

- I. ^ In this context, the term "campesino communities" refers to the social and political organizing of land workers to defend their rights and interests. Campesino communities seek to impro

- II. ^ "Ejido" is a fundamental concept in Mexican land tenure and agrarian law. It refers to a specific type of communal landholding where the land is owned by the state but is granted for use to an organized group of rural inhabitants, the "ejidatarios."

- III. ^ Workers in a "maquiladora" are employed in a factory—often foreign-owned—that operates under special regulatory agreements. Their job involves assembling, processing, or manufacturing goods using imported parts, with the finished products then being exported for international sale. In these paragraphs, the term "maquiladora" is used metaphorically to describe Mexico's role in the digital economy (as "maquiladores" of infrastructure or "maquiladores" of data). This contrasts with the traditional meaning, which is focused on physical product assembly.

- IV. ^ "Gaceta Municipal" is the official, regular publication a municipality uses to communicate its legal and administrative decisions. Its core function is the formal promulgation of regulatory provisions, ordinances, programs, and administrative notices, ensuring that the population is duly informed and enabling the proper application and observation of the law.

- V. ^ Evaluación de Impacto Ambiental (EIA) is an administrative and technical process required by law that outlines the potential significant effects a proposed project, plan, or program might have on the environment before it can start. Its goal is to provide authorities with the necessary data to prevent, minimize, or repair environmental damage, such as harm to air, water, soil, wildlife, and public health.

- VI. ^ "Acta del ayuntamiento" is a formal document detailing the agreements, debates, and final decisions of a municipal council or town hall meeting.

- VII. ^ Manifestación de Impacto Ambiental (MIA) is the technical and legal report that projects or activities with potential environmental consequences must provide for official review. To clarify the terms: the EIA is the entire evaluation process, and the MIA is the primary document used within it.

- VIII. ^ In Mexico, the acronyms EIU (Estudio de Impacto Urbano) and EIV (Evaluación de Impacto Vial) refer to planning and public policy tools. They are used to evaluate and regulate urban development and construction projects.

- IX. ^ "Ficha oficial de emplazamiento" is a municipal document detailing the urbanistic and legal parameters governing a designated plot of land. This document is crucial for due diligence, specifically for validating compliance and regulatory viability prior to the execution of a development or building initiative.

- X. ^ Registro Agrario Nacional (RAN) is a decentralized government agency that controls and documents communal and ejido land tenure, providing legal status as stipulated by the Agrarian Law.

- XI. ^ The "LX Legislatura de Querétaro" was the legislative body of the state of Querétaro from September 26th, 2021 to September 25th, 2024. Its main functions, like those of any local congress, were law-making, financial oversight of the executive branch (via budget and public accounts), and citizen representation.

- XII. ^ Comisión Estatal del Agua (CEA) is the state-level agency tasked with overseeing and executing all programs related to water management, infrastructure development, and sanitation.