Big Tech, Big Agro, Big Money: technologies of dispossession and the digitalization of monoculture in Brazil

By Mariana Tamari and Joana Varon1 . Matopiba, BRAZIL

Coding Rights

Research collaboration: Antônia Laudeci Oliveira Moraes

Illustration: Giovanna Joo

English translation: Luisa Barraza

LAND

"Although creatures of nature, Humanists detach themselves from it and position themselves as creators. Hence their need to synthesize the organic, to reduce all life to raw material. This raw material becomes an object that must be improved, refined, and synthesized by humans. They feel they are masters of intelligence; they feel they are gods—gods in the logic of verticality, in the logic of power, of interference in the lives of others, and of manipulation."

Antônio Bispo dos Santos in “The Land Gives, the Land Wants» [La tierra da, la tierra quiere]”

Visions of the Future?

Trapped in cages, meant to keep visitors at a safe distance, the drones take flight in front of a curious and enthralled audience. Their headlights switch on. Shaped like watchful eyes, they give the machines a lifelike, angry appearance, as if they were ready to strike. In fact, after a few seconds of flight, the "creature" begins to spray a liquid. For demonstration purposes, it is only water. In practice, however, the machine is sold for dispersing pesticides—sometimes including substances among the more than 500 agrochemicals banned in the European Union but still permitted in Brazil.2

Drones displayed in cages were a recurring sight at various stands at Agrishow, one of the three largest agricultural technology fairs in the world and the largest in Brazil. The event takes place annually in May in Ribeirão Preto, the city known as "the national capital of agribusiness" in the interior of São Paulo. This city hosts the headquarters of the sector's largest companies, including multinationals like Syngenta, Bayer, and BASF. This year the Agrishow, recognized as the stage for the main launches and technological innovations in agribusiness, received approximately 197,000 visitors over the course of its five days.3We were among them.

Wandering across the fair's 52 hectares—roughly the size of 73 soccer fields—we visited the stands of major national and international agricultural companies, replete with gigantic machinery resembling the spaceships of science fiction. Meanwhile, on the clay floor where the fair was set up, the only green that stood out was the glow of LED panels, creating parallel virtual realities—proudly showcasing equipment focused on the digital transformation of agribusiness—all promising great things. What imaginaries of the future and technology do large agribusiness companies promote? How does this vision accelerate monoculture, threaten crop diversity, and compromise our food security? To explore these questions in further depth, this study moves between two territories: the Agrishow in Ribeirão Preto, where we map the technological imaginaries of the future of agriculture; and the Matopiba region, where we interviewed researchers and land defenders. The portmanteau Matopiba refers to the Brazilian geoeconomic region comprising the states of Maranhão, Tocantins, Piauí, and Bahia. This region is known as “the new agricultural frontier”, where the digitization and implementation of some of the technologies showcased at Agrishow are already posing new challenges in regard to long-standing agrarian conflicts and how they are managed. We focus on the case of Gleba Tauá, in Tocantins, where traditional populations are facing territorial conflict with soybean monoculture agribusiness. From land ownership to cultivation methods, through field experience and conversations with agricultural researchers and territorial defenders, we set out to raise questions about the impacts of the digitization of the countryside—pushed by Big Money, Big Agro, and Big Tech. But let us return to Agrishow:

The forest eaters' technosolutionism

"Precision farming", sensors, remote monitoring, automation, prediction... The "Agro of the future"—that was the promise on display. The combined power of heavy machinery, data intelligence, digitization, and artificial intelligence was marketed as a magic solution for every problem Big Agro's monocultures might face: drought, soil degradation, pests, labor shortages, and climate change. In the narratives sold at Agrishow, there is no climate collapse; only an abundant future, thanks to technology.

The promise is that rural areas, blanketed with different types of sensors sold in smart farming kits (marketed as discounted combo packages), will become fully accessible via a screen. With machinery operated remotely via cell phone or computer monitor, farming takes on the dimensions of a video game:

In this vision of the future, the presence of humans in direct contact with the land no longer prevails. There will be no place for empirical knowledge of the territory, often passed down orally from generation to generation. Relationships—whether professional, commercial, emotional, or with nature—are structurally altered: they are now reduced to data, collected and processed by algorithms stored in the so-called "cloud."4This cloud promises solutions for every problem and every business, as long as it is some type of monoculture; primarily soybean, corn, cotton, or sugarcane. According to this narrative, traditional communities and land conflicts practically disappear in satellite-generated imagery, despite remaining deeply rooted in the territories. They are not recorded on the operator's monitors and are ignored by digitized public authorities.

One idea in particular dominates the advertising slogans: that new technologies can be used to control nature and maintain profit: "From planting to harvest, everything is under control," "Agrointelligence," "Turn data into profit," and "Evolving is natural."

These displays are almost caricatures of what renowned science and technology philosopher Donna Haraway criticizes as one of the frequent responses to "the horrors of the Anthropocene and the Capitalocene": the comic faith in techno-solutionism—a mindset also widespread among CEOs of Big Tech in Silicon Valley. As Haraway writes, "Somehow, technology will come to the rescue of its mischievous but very clever creatures!" (Haraway, 2003: 12). What Haraway called "comical" may in fact be more of a business strategy. Ultimately, these discourses are, once again, expressions of the warlike narrative of the hero, where man—this heroic and intelligent being—uses his weapons and technological tools to control and dominate nature, an external force of which he is not a part. This narrative has been yielding profits for decades.

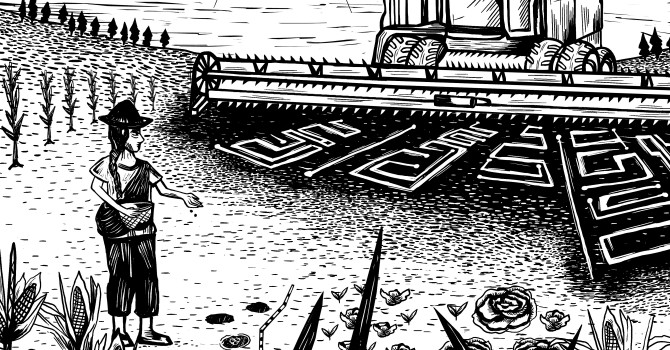

From urban areas to the countryside, large technology companies consistently promise that automation will require less labor (and fewer labor rights). In the countryside, machines are growing larger every day, keeping pace with the increasing size of plantations, the expanding areas devoted to agribusiness, and, consequently, land concentration. After all, the convergence of Big Tech and Big Agro narratives equals Big Money. The large combine harvester shown above, equipped with a corn harvesting platform,5 is considered economically viable for properties ranging from 100 to 300 hectares, an area the size of around 140 to 420 soccer fields. The company even sells a larger model, featuring more collection lines, recommended for properties ranging from 300 to 500 hectares. This huge machine, which could be the cousin of a Transformer from the 1980s science fiction series, is capable of mastering gigantic tracts of land.

The acclaimed speculative fiction writer Ursula K. Le Guin—whose work is deeply influenced by feminism and cultural anthropology—offers, in The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction, a fundamental critique of the traditional heroic narrative, one centered on the "weapon," the tool of hunting, conquest, and conflict that dominates Western storytelling. Le Guin argues that the cultural obsession with narratives of armed heroes, epic adventures, and violent conflicts reflects a masculinized and limited view of human experience. These stories privilege action, conquest, and domination, marginalizing everyday experiences of care, cooperation, and life sustenance. To center these other experiences, the author proposes an alternative based on the "bag"—the container that collects, preserves, and sustains life. For her, the "bag" represents a different way of storytelling, one focused on what nourishes communities: domestic work, food gathering, caring for children and the elderly, and the preservation of knowledge. Le Guin argues that these activities, historically associated with women, are more fundamental to human survival than heroic hunting dependent on weapons and other tools. But what happens when even the bag that collects food for nourishment is replaced by these large machines for monoculture?

In The Falling Sky: Words of a Yanomami Shaman [La caída del cielo: palabras de un chamán yanomami6], Davi Kopenawa uses the term "forest eaters" to refer to the destructive relationship that the napë (white people or foreigners) have with nature, "devouring" the forest through deforestation, mining, intensive agriculture, and other activities that consume and destroy the environment. With increasingly larger machinery and the promise of precision and predictability sold by narratives of digitization and future-oriented technological imaginaries, the mouths of these forest eaters are growing bigger and more voracious.

The worst part is that this food is not for everyone. In 2024, Brazil—which has just over 200 million inhabitants—produced enough food to feed 800 million people, as per data from Embrapa, Empresa Brasileira de Pesquisa Agropecuária (Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation).8. According to the Brazilian Confederation of Agriculture and Livestock, the country is the largest exporter of soybeans, coffee, orange juice, sugar, cotton, beef, and chicken; and is the second largest exporter of corn and the fourth largest exporter of pork9. Despite this, data from the United Nations' Report on the State of Food Insecurity in the World (SOFI 2024) suggests that 14.3 million Brazilians are in situations of severe food insecurity10. This is because, as a colonial legacy, financial investment in Brazil's agricultural production—and in the technologies showcased at Agrishow—is directed towards export-oriented monoculture. The "commodity people" are, to use Kopenawa's terminology, those same "forest eaters". The sector's significant economic influence (about 23% of Brazil's GDP) and its political power (the Parliamentary Agricultural Front, FPA currently holds over 50% of the seats in the National Congress) gives us a sense of the weight carried by the "Agro future" narratives marketed at the fair's stands.

Intergenerational narratives ensuring patriarchal futures of human dominion over nature

Walking among the stands of more than 800 exhibiting brands, we could clearly see the importance of building up a narrative and imaginary that exalts Agro—along with its practices and technologies for all generations, from grandfather to grandson—was undeniably obvious. All men, since only men were featured in the marketing materials. Intergenerational agrotech appeared in advertisements, in the design of the booths, and even in the shops selling clothes, accessories, and toys—like the tractor below, displayed with a mechanical arm capable of cutting and uprooting a tree. Why should children play at uprooting trees?

In her book Banzeiro Okotô, journalist Eliane Brum highlights the important role of fabricated imaginaries in enabling the destruction of the forest. She points out that "the corporate-military dictatorship (1964–1985)—which initiated the first large-scale project of forest destruction—expanded, strengthened, and relied heavily on this false narrative. To do so, its generals launched an ad campaign that cemented the image many still hold today: that the Amazon was an untouched, virgin land (…) The most shameful slogan of that era was: 'The Amazon, unmanned land for men without land'" (Brum, 2021: 27). Brum concludes that: "the idea of the forest as a body to be violated, exploited, and plundered has not been abandoned by any of the governments of Brazil's restored democracy since the 1980s." (Brum, 2021: 29)

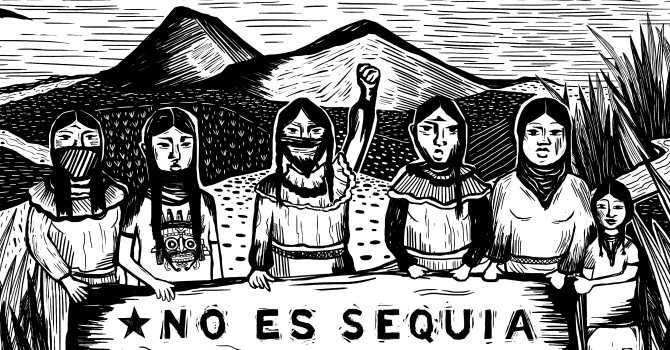

This imaginary, clearly evident at Agrishow, perpetuates the idea of the virgin forest, of nature to be dominated, of the forest and other biomes as a body to be violated. In Brum's words: "the moral dogmas that constitute the pillars of white supremacy, patriarchy, and gender binarism also sustain the capitalist model that has devoured nature and led the planet to a climate emergency. These are not two different projects; they are one and the same" (Brum, 2021: 37). It is no coincidence, therefore, that the voices of Indigenous women—quilombolas11, ribeirinhas, and other land defenders—are among the most prominent in the socio-environmental justice debate. Agrishow, in fact, was such a blatant display of patriarchy that, even though we have the skills and interest in tools and technology, the scenes—dominated by men and machines—were hard to digest. What was being served up was pure, concentrated patriarchy, and it is something we neither want to, nor should, swallow.

The toxic narrative of Agrishow's technosolutionism is intertwined with that of the Anthropocene, which universalizes the anthropos (human) and "hides the systemic intersection of racism, colonialism, heteropatriarchy, social inequality, and human supremacy in the driving of the current planetary crisis" (Armiero, 2021: 18). The narrative of an Agro industry that is tech-driven, modern, automated, precise, efficient, and rational represents a vision of the future that authorizes "the commodity people" to continue "eating the forest, dominating nature," and "bringing modernity and civilization," now with the magic of digital technologies and artificial intelligence that will—without repairing the past or adjusting the course of its production model—lead to "regeneration" and "sustainability."

We propose not that notions of regeneration and sustainability be abandoned, obviously, but that the offering of simplistic solutions in response to complex problems should be viewed in a critical light. Likewise, in the face of climate collapse, we must avoid the opposite extreme of technosolutionism: falling into the idea that everything is over. Haraway, who is also a biologist, states that "there is a fine line between recognizing the extent and severity of problems and succumbing to abstract futurism with its affections of sublime despair, and its politics of sublime indifference" (Haraway, 2023: 14). Instead of these two extreme responses, she invites us to "stay with the trouble"—to live and die “responsibly” on our damaged planet, avoiding the easy fix of technofuturism, and instead creating "unexpected kinships" with other species. The problem is that "staying with the trouble" doesn't sell nearly as well as "solution markets" like Agrishow.

Money is not the issue

According to the Agrishow website, the 2025 event generated "a record R$14.6 billion in business interests, marking a 7% increase over the R$13.6 billion generated in 2024."12 It is no coincidence that the abundance of credit lines and public-sector investments in agribusiness was visible even in the layout of the fair: there was an entire block dedicated exclusively to banks offering different financing options.

As technosolutionist narratives converged, major Silicon Valley technology companies—known as Big Tech—wasted no time in securing a significant share of these investments. Numerous examples illustrate direct partnerships between Big Tech and multinational agribusiness giants, a trend expected to expand further as AI is increasingly applied in the digitalization of Big Agro. Just to name a few: Microsoft has a direct partnership with the massive corporation Bayer.13. The company has also launched a program for AgTech startups, offering up to $120,000 in Azure credits, its cloud computing platform. Amazon and Google likewise collaborate as providers of critical digital infrastructure for large agribusiness companies such as John Deere, Syngenta, and BASF, supplying AI, cloud computing, and analytics that power specialized agricultural platforms. IBM, SAP, and Oracle consistently appear as leading providers of agricultural analytics, working with giants like ADM, Cargill, and other multinational agribusinesses to implement integrated data management and analysis solutions14.

Driven by the financial market, the productive and economic alliances between Big Agro and Big Tech consolidate billions in capital, enabling them to absorb smaller companies and producers, posing a threat to the sector's diversity. Agroecological technology faces both practical pressures in the territories and epistemological pressures—driven by the allure of technosolutionist imaginaries of monoculture and the massive resources directed toward Agriculture 4.0, which aims for the full digitization of agricultural processes. A narrative has taken hold suggesting that alternative practices, such as agroecology, are outdated and technologically deficient. There is no looking back, and no acknowledgement of other agricultural practices that are already integrated with what the land provides.

Archaeologist Eduardo Góes Neves traces eight thousand years of history in the Central Amazon in his book Sob os tempos do equinócio (Under the Times of the Equinox), showing that, contrary to the narrative of a "land without men," Indigenous peoples have inhabited the territory now known as Brazil for over 12,000 years. Neves also highlights findings from soil research, which show that "the use and management of resources in the Amazon were characterized by diversification, rather than the exhaustive exploitation of a few resources (...) from the beginning, the Indigenous peoples of the Amazon engaged in the cultivation of various plants, many of which are still consumed today, such as cassava and Brazil nuts, initiating agrobiodiversity practices that continue to this day" (Neves, 2023: 60). Quilombola leader Antônio Bispo dos Santos describes similar yet distinct self-management practices in his "community of Afro-confluent families", thousands of years later. Agriculture has always been practiced there, although "no one had land; they had crops" (Santos, 2023: 90). Bispo recounts in his book A terra dá, a terra quer (The Land Gives, the Land Wants): "So we threw all kinds of seeds in the same place and the land selected the seeds it would let germinate. Some animals, known as insects, preferred to eat one species of plant and left the others. That was the cosmological wisdom of our people. We didn't need to use poison because the animals did the selecting for us. Since all plants were food, those that remained were for us. Our people also said that the earth gives and the earth wants. When we say this, we are not referring to the earth itself, but to the earth and all its compartilhantes." (Santos, 2023: 91)

Bispo faced this territorial and epistemic clash, sowing words in what he calls the war of denominations. For him, being a compartilhante (co-sharer) refers to circulation rather than accumulation, to orality and confluence as a form of resistance. Body, territory, ancestry and non-human knowledge all converge...By identifying cosmophobia as "the great disease of humanity" (Santos, 2023: 29), he critiques a worldview based on fear of nature—one that guides anthropocentrists and their accumulation and storage model, generating waste, rubbish, and death. He says: "My grandmother used to say that, just as the best place to store fish is in the river, the best place to store cassava roots is underground. However, they began to put down poison, and the wild animals started to die. You throw poison on the insect, it dies, but the animal that feeds on the insect also dies. We no longer have fish in the rivers because they throw poison on the crops during the spawning season, when the fish reproduce. When the first rains come, the poisoned water flows into the spring and kills the fish—both small and large—and prevents reproduction. It is death en masse." (Santos, 2023: 85)

Just days after visiting Agrishow, we held a field interview with Matopiba territory defenders who confirmed reports of drones—similar to those mentioned earlier for the dispersal of pesticides—being deployed on family agriculture lands; a tactic employed by large monoculture enterprises as a means of expelling small rural producers. Drones have become now an agribusiness "solution," used to make space for seeding the imaginary and toxic narrative of monoculture. A critical vision is urgently needed—one that questions the imaginaries being sold at Agrishow and instead strengthens practices and imaginaries grounded in care, responsibility, and commitment to resistance and existence beyond technologies that seek to control bodies, minds, and territories. These resistances have existed for centuries; they simply need to be heard.

At the beginning there was fire

Among those interviewed for this study, we spoke with Vinicius Gomes de Aguiar, a professor and researcher from the Federal University of Northern Tocantins (UFNT). When we asked Aguiar how he viewed the use of technology in expanding agricultural frontiers in Matopiba, he replied: "Fire is still the most commonly used technology for agribusiness expansion."

Besides teaching at UFNT, Vinícius is a member of Neuza - Núcleo de Pesquisa e Extensão em Saberes e Práticas Agroecológicas (Center for Research and Extension in Agroecological Knowledge and Practices), works at the Superintendência Federal de Desenvolvimento Agrário, SFDA, in Goiás (Federal Superintendence of Agrarian Development), which is linked to the Ministério do Desenvolvimento Agrário, MDA (Ministry of Agrarian Development), and is part of the Observatório de Conflitos Socioambientais do Matopiba (Matopiba Socio-Environmental Conflicts Observatory). 16

Comprising the state of Tocantins and parts of Maranhão, Piauí, and Bahia, the Matopiba region derives its name from a portmanteau of those four states. Since the mid-1980s, this area has seen intense agricultural expansion, primarily for grains such as soybeans, corn, and cotton. Its flat topography, legal gaps in land regulation, and the low—or near-zero—cost of land compared to established areas in the Center-South, have driven many rural producers to seek out this area.

Matopiba is largely situated within the Cerrado biome, which is also where agricultural expansion is most pronounced. About 66.5 million hectares (91% of the region) fall within this biome, while smaller portions lie in the Amazon (5.3 million ha, 7.3%) and the Caatinga (1.2 million ha, 1.7%). Its climate is mostly semi-humid tropical (covering 78% of the territory), with high temperatures resulting from its low latitude and low altitude. An exception is western Bahia, where temperatures tend to be milder due to the higher altitude15. This is the typical Cerrado climate, with average temperatures above 18°C throughout the year and dry periods lasting 4 to 7 months, generally coinciding with the winter semester (which starts in June). The alternating dry and wet seasons, along with the savanna vegetation, contribute to the spread of fire—especially during the dry months—but natural causes are far from the main driver of deforestation in the Cerrado within Matopiba.

From January 2023 to July 2024, deforestation in the Brazilian Cerrado emitted 135 million metric tonnes of carbon dioxide (CO₂, the main greenhouse gas), exceeding the emissions of Brazil's industrial sector, according to data from the Sistema de Alerta de Desmatamento do Cerrado, SAD, in the Cerrado (Cerrado Deforestation Alert System),[14] developed by the Instituto de Pesquisa Ambiental da Amazônia, IPAM (Amazon Environmental Research Institute). Of these emissions, 80% originated in Matopiba, a region that saw more than 2.7 million hectares deforested between 2019 and 202317.

The Relatório Anual do Desmatamento, RAD in Brazil (Annual Deforestation Report),19, produced by Map Biomas, pointed to an 11.6% decrease in the total deforested area in Brazil in 2023, with the Amazon and Cerrado, the country's two largest biomes, accounting for more than 85% of this area.

That year, the Cerrado surpassed the Amazon for the first time, becoming the biome with the largest deforested area, totaling 1,110,326 hectares—an increase of almost 68% over the previous year. In contrast, the Amazon saw a 62.2% reduction in its deforested area. The report also highlights that Matopiba alone accounts for 47% of all native forest loss in the country.

The reduction in deforestation of the Amazon biome in recent years is excellent news. As a result of growing awareness of climate change, the Amazon rainforest is in the spotlight of major international conservation movements and organizations, and has benefited from the mobilization and centuries-long struggle of traditional, Indigenous, quilombola, ribeirinhos, and other forest peoples who, despite the disparity of forces, have gained visibility, even occupying more space in political power and decision-making in recent decades. Although still far from representing a solution for the biome or a concrete response to the climate and environmental crisis, this mobilization manages to provide some protection for the forest.

"The Cerrado, for its part, has been increasingly affected by agribusiness. While the discourse that the Amazon rainforest must be preserved is gaining strength—as, of course, it should—the Cerrado is becoming the main sacrifice zone," explains Vinícius.

Despite being the biome where the heart of Brazil's waters beats—home to the headwaters of eight of the country's 12 main river basins and responsible for the water cycle that carries the Amazon's "flying rivers" to the south-central region, and boasting the most biodiverse savanna on the planet—the Cerrado has become the latest sacrifice zone20.

The Cerrado's status as a territory vulnerable to devastation was cemented with the approval of the 2012 Forest Code. The legal allowance to reduce the reserva legal II on rural properties by up to 80% across most of the biome essentially allows for the destruction of native vegetation and traditional ways of life and paves the way for monoculture, irrespective of the socio-environmental criteria that should guide the authorization of vegetation clearance.

Another point is that many areas of the Legal Amazon are public lands under federal government jurisdiction, which allows for greater management and governance capacity through environmental agencies such as the Instituto Brasileiro do Meio Ambiente e dos Recursos Naturais Renováveis, IBAMA (Brazilian Institute of the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources) and the Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade, ICMBio (Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation). In the Cerrado, most environmental responsibilities fall to state and local agencies, which are highly vulnerable to political and economic pressures in their territories. This often results in policies that favor the rapid expansion of agribusiness, particularly in the Matopiba region.

Vinícius also links the Cerrado's status as a sacrifice zone to the use of fire as the primary technology for expanding the agricultural frontier: "Obviously, to occupy these areas, they need to give the impression of making them productive. Productive by their own understanding, right? In this sense, agroforestry or mata em péIII is a problem for agribusiness. It is not productive, it does not yield the same profit. So you need to remove that forest to make a path for monoculture, for agribusiness, and fire makes this clearing process faster. After the fire, they build a fence and so on. This allows the cattle to advance, creating a first opportunity for expansion. In our research, we began to notice this behavior in conflicts, especially on the part of grileiros (land grabbers), the people who try to remove traditional communities from their territories, using fire for this purpose," he concludes.

By observing the use of fire for certain purposes, it becomes clear that there are strategies, planning, and deliberate control of fire as a technology for illicit territorial expansion. Vinícius cites data from MapBiomas Fogo showing that, proportionally, within the Matopiba region, Indigenous lands—despite being largely regularized—were the areas most affected by fires in 2021, 2022, and 2023. On average, about 22% of Indigenous lands burned, while only 6% of Matopiba as a whole was affected. Vinícius hypothesizes that fires advance onto Indigenous communities because agribusiness believes certain ethnic groups should not have rights to the land—especially when they maintain it in a state of preservation. "If you want to keep the land, it has to be in line with the principles of agribusiness. If your aim is preservation, then they will come after you to show you how it should be done."

Vinícius, who is also a researcher at Neuza, contradicts, however, the frequently used argument that fire and devastation are caused by traditional communities. There is empirical and documented knowledge of traditional communities in the Cerrado, who use fire as a technology for managing their territory. "It is common, for example, to use controlled burns to prevent larger fires and to train fire brigades. In Maranhão, in the region of the Chapada da Serra das Mesas National Park, there are courses with quilombola communities on how to work with fire. They know the power that fire has when it is not controlled. These people and communities have mastered fire, so they shouldn't have any problems, right? But when we look at major accidents, large-scale fires, we realize that it is not the same technology being used."

After the fire, the cattle, the machines, and the violence

Expulsion technologies and the case of Gleba Tauá

The agroecological lifestyles and production methods of traditional communities, including the mata em pé, are not productive or profitable enough within the current agro-export business model. Consequently, besides the use of fire, other technologies are deployed to drive communities out of rural and forest, paving the way for agribusiness monocultures and preparing the terrain for highly profitable, digitized agriculture.

Once the land is burned, cattle are let loose, and heavy machinery—such as that used in correntãoIV — cuts down trees on a massive scale. The traditional communities inhabiting these territories are violently expelled through fires that destroy their homes, physical and psychological aggression from grileiros' henchmen, or the invasion of their small properties by cattle. In addition, the indiscriminate spraying of pesticides spreads poison not only over the crops, but also into neighboring communities, contaminating people, animals, and food sources.

Next, the soil is prepared with massive plows, planters, and irrigation pivots. This is the first step in building a truly dystopian scenario: one of high mechanization and digitization in the countryside, further pressuring local populations and agroecological producers by deploying remote-controlled machinery, drones for pesticide application, and predictive software. These technologies and processes intensify and accelerate both the imbalance of power and the concentration of land and income in rural regions.

Matopiba, the primary frontier of Brazil's agricultural expansion today, is emblematic of this process. Within it, we examine the case of Gleba Tauá—a traditional territory in the state of Tocantins that has been occupied since the 1950s by rural families who migrated from Maranhão and Piauí. Here, a wide range of technologies and methods are deployed to expel the community and make way for soybean monoculture. At the same time, this micro-region is also a center of intense resistance and struggle by traditional families—the original posseirosIV — who are fighting to maintain their communal way of life and protect their lands in the Cerrado.

Recognizing the vulnerability of this large area of federal land where families without title deeds lived, Santa Catarina soybean producer Emilio Binotto and his family invaded Tauá in 1992 and embarked on an ambitious process of grilagem das terras (land grabbing). The farmer is currently involved in a legal dispute with the Gleba Tauá community, in a conflict marked by illegality, violence, destruction, deforestation of the Cerrado, and coercion of the community.

Researcher and professor Antonia Laudeci Oliveira de Moraes is a member of the graduate program PPGCUL and Neuza– UFNT. She also worked for the Comissão Pastoral da Terra, CPT (Pastoral Land Commission) in Araguaia-Tocantins for 10 years and closely followed the life and struggle of the community in Gleba Tauá. This area also became the focus of her academic research. In this case study, Laudeci collaborated with Coding Rights, drawing a parallel between the story of Tauá's political and matriarchal leader, Dona Raimunda, and the struggle for territory. Laudeci also assisted with data collection and specific interviews.

In her Master's thesis, Laudeci weaves together Dona Raimunda's life story with the broader struggle of rural working women living under patriarchy and their role in resistance movements, specifically within the Gleba Tauá community. Laudeci highlights Dona Raimunda's fight for land ownership and her leadership in these movements, reflecting on how her life and legacy contribute to our understanding of the territorial struggle faced by traditional communities in Tocantins. Laudeci explains: "Dona Raimunda's narratives and reflections show that the Binottos, since their arrival, have consistently attempted to strip rural families of their right to live on the land, transforming Dona Raimunda's place of peace into a site of intense conflict where there were threats to her life (...) Dona Raimunda became a symbolic, crucial leader in the resistance against soybean expansion and the fight for territorial rights. Her life is deeply marked by a connection to the land and a commitment to preserving her family's traditions, thereby making her a central figure in mobilizing the community and denouncing rights violations in Tauá."

For this article, Laudeci compiled a series of more than 20 police reports. These had been filed with the Goiatins-TO police station between 2022 and 2023, by members of the Gleba Tauá community against the Binotto family and their henchmen. They outline the violent methods of intimidation and aggression used in grilagem, as also reported in the CPT's Cadernos Conflitos no Campo (Conflicts in the Countryside Notebooks).22.

One of the complaints—collectively filed by the Associação dos Produtores da Agricultura Familiar da Gleba Tauá (Association of Family Farmers of Gleba Tauá)—denounced the farmers' modus operandi regarding the residents of Tauá:

"The complainant appeared at this Police Station on the date/time mentioned above, on behalf of the members of the Gleba Tauá Family Farming Producers Association, to report that the members of the aforementioned legal entity are victims of Unlawful Possession on their rural properties. As a result of the perpetrators' actions (or modus operandi), the properties' reserva legal are currently being deforested. The complaint states that, as of December 2022, the perpetrators began to invade the farms of the association's members, using a tractor to 'drag' and chains to 'break' the vegetation. THAT after committing these acts, the perpetrators left the site, stating they would return to 'fence everything in.'"

In another case, a resident of Tauá recounts how grileiros use cattle to destroy crops, attacking and intimidating small farmers:

"The caller reports that Pedro Amaro and other people are putting several animals within the boundaries of her farm, and these cattle are causing considerable damage for the victim, eating her crops and preventing her children from going to school, because these animals are very aggressive. There is a court injunction prohibiting these people from continuing the work, however they are not obeying the order."

In recent years, however, the Binotto family has escalated its tactics beyond using cattle to destroy crops and intimidate the Gleba Tauá community. There are reports that drones have been systematically used to spray poison on agroecological crops, residents, and the community water supply. Drones are also used as surveillance and intimidation technologies, as Laudeci recounts from reports collected for her Master's research with Dona Raimunda: "With the use of drones, they are able to spray poison and observe the territory whilst also terrifying people. These are people who do not have access to technology, who do not know what a drone is–especially the elder matriarchs and patriarchs of the community. Agriculture is acquiring more technological tools, and communities are becoming increasingly trapped."

Community members reported several cases to the CPT involving the use of drones, saying that they systematically circle around houses, flying next to the windows, night and day. Even over bathrooms: "Look, you know, it's uncomfortable, us being in the bathroom and that thing flying over us while we're in there," Dona Raimunda told Laudeci.

Dona Marlene, another long-time resident of the Serrinha community, near Tauá, told Laudeci what happens when pesticides arrive on their land: "Things are much more difficult now, because the big operators are stepping on the little guys. It's not that they come here just to trample our crops, no. It's that they have soybean and corn fields right over there. And when they prepare that land, what do they put on it? Poison. That poison doesn't stay there; it comes with the wind and gets onto our plants. It also comes with the water, through the floods, passing underground. And now, most of them aren't even using planes anymore—they're using drones to spread the poison."

The violent use of drones for pesticide spraying, aimed at destroying family crops in Gleba Tauá, carries consequences that extend beyond simply making the land unproductive for agroecology. As Dona Marlene explains, all the social technology she learned from her ancestors is lost. "My mother used to gather these leaves, and I got tired of helping her. She would set them on fire, mix them together, throw water on them so they wouldn't turn to ash. Then she would take chicken manure and mix it in, you know? Together with the cattle manure, the cow dung, she would mix those three fertilizers together and put them in that large garden bed by the river, like this, wow, when I remember it, I get emotional… Those large garden beds by the river, like this, with peppers, tomatoes, onions, and cilantro. She planted everything, you know? And that was it. Today we do that—I've done it the same way—and nothing comes."

The CPT Araguaia Tocantins, where Laudeci worked for 10 years, monitors around 30 communities in the northern region of the state. According to her, virtually all of them live in a constant situation of land conflict. And in every one of them, connectivity is extremely precarious—or nearly nonexistent.

"Often, the families, the people suffering violence, do not even have a way to call for help during a moment of conflict, because they are in places that have no internet signal, where cell phones don't work, and where they cannot call to the police—they are isolated" says Laudinha. These are populations that, in addition to lacking access to digital technology, suffer further exclusion and violence at the hands of grileirosand large landowners who actively employ these strategies. "Imagine people who don't even have cell phone reception, the fear, the pressure they feel when they see something flying overhead and filming their home, or when they see a huge driverless tractor. It's very unfair, very oppressive," she adds.

Digital land grabbing: the pressure of invisible fences

Parallel to all this is the historical process of misappropriation of land, known in Brazil as grilagem de terras, which makes these disputes and conflicts even more violent. This is a form of symbolic and patrimonial violence that is especially difficult to combat, as it is rooted in political and economic power. In this context, the digitization of land governance also deepens inequalities and facilitates the erasure of traditional communities, forest ways of life, and conflicts within these territories. Grilagem digital (digital land grabbing) is now a great spectre haunting the struggle for land and territory in Brazil.

What is grilagem de terras?

The term 'grilagem' (land grabbing) has its roots in an old practice of document forgery. To give documents the appearance of old land titles, fraudsters would place the forged papers in boxes with crickets (grilos). The insects, by gnawing and defecating on the paper, gave it an aged appearance, thus lending false legitimacy to the titles.

Today, grilagem refers to any illegal action intended to transfer public land into private ownership. This practice exploits weaknesses in Brazil's land tenure system, which lacks a unified property registry for integrating municipal, state, and federal records. The absence of effective oversight over large landholdings also facilitates the actions of grileiros (land grabbers).[21]

Currently, fraudsters exploit loopholes in multiple official systems: they register titles in notary offices, illegally declare properties to the Receita Federal (Brazil's federal tax authority), and submit data to land agencies through digital environmental-control systems (we will discuss digital land grabbing later). By triangulating this scattered information, they manage to create an appearance of legality for lands that are, in fact, public, or belong to traditional communities. This strategy turns grilagem into a complex crime that capitalizes on institutional fragmentation to sustain itself.

In this context, power relations between large landowners and public authorities have always given the former a significant advantage over traditional communities, Indigenous peoples, and poorer populations. Brazil has never undergone land reform, and the result is a land tenure structure that is profoundly unequal and chaotic. But this "chaos," far from being accidental, serves very specific interests. Within this scenario, a technosolutionist narrative reappears as a quick and easy answer to the centuries-old problem of land distribution and land regularization—yet once again, it deepens inequalities and fuels further conflict.

The Brazilian Rural Environmental Registry: from environmental regularization to digital land grabbing

The Cadastro Ambiental Rural, CAR (The Rural Environmental Registry) in Brazil is a mandatory national electronic public registry for all rural properties, created by Law No. 12,651/2012, established by the new Forest Code. It was conceived as a key tool of the Programa de Regularização Ambiental, PRA (Environmental Regularization Program),23 with the purpose of integrating environmental information on properties, such as permanent preservation areas, reserva legal, and remnants of native vegetation. To centralize this data, the law established the Sistema Nacional de Cadastro Ambiental Rural, SICAR (National Rural Environmental Registry System). The initial aim of the CAR was to support the Public Administration in controlling, monitoring, and planning environmental and economic activities, especially in combating deforestation and promoting the environmental compliance and regularization of rural properties. Over time, however, the Registry has increasingly come to be used as a mechanism for land regularization, facilitating access to benefits such as rural credit, technical assistance programs, and financial incentives.

According to Karina Kato, professor and researcher at the Federal Rural University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRRJ)'s Graduate Program in Social Sciences in Development, Agriculture, and Society (CPDA), “the increasing digitization of public policies, especially those related to land registration, reflects a profound change in the role of the State. Whereas the government once played a central role in formulating agricultural technologies and policies—as was the case with Embrapa in the 1970s—it now tends to absorb and adapt tools developed by the private sector. The CAR (Rural Environmental Registry) is an emblematic example of this transformation. Initially conceived as a private-sector initiative tested by agribusiness in regions such as Mato Grosso, the CAR was later incorporated by the State into public policy. It began to be used to verify the 'sustainability' of soybean and cattle production, in addition to being increasingly employed in land regularization, despite its well-known flaws. This shift—from policies grounded in territorial rights (agrarian reform; recognition of quilombola and Indigenous lands) to a digitization-driven approach focused on land regularization—has ultimately accelerated the privatization of public lands."

The use of tools such as the CAR is part of a broader framework of digital land governance, presented as a solution to land conflicts and environmental protection issues. In practice, however, resources that were once allocated to agrarian reform are now redirected toward the creation of territorial information systems that prioritize rapid land regularization over social justice. Because the CAR is self-declared and fully digital, it has enabled a process of grilagem digital (digital land grabbing). This not only facilitates and accelerates the illegal appropriation of territories, but also erases conflicts—and the very existence of traditional communities and their ways of life—through satellite-generated imagery, large automated agricultural machinery, and the algorithms operating behind cell phones and computer screens.

Larissa Packer, a researcher at UFRRJ and with GRAIN—an NGO that supports family farmers and social movements fighting for biodiversity-based and community-controlled food systems—was updating data on land concentration in the Southern Cone when she noticed a pattern: every country she worked in was either building or implementing digital land registries, and every process was marked by conflict. She states: "I saw that several countries were implementing digital land registries, many of them based on self-reporting and without sufficient State capacity to verify the information. Field visits by technicians were being replaced with remote monitoring—whether by drones, satellite imagery, or artificial intelligence." According to Packer, this approach fails to assess whether a territory fulfills its socio-environmental function, as required by constitutional law. A satellite image can show deforestation and occupation, but it cannot reveal whether land grabbing involved violence, whether possession is historical or recent, or whether the transfer of public land to private hands is legitimate.

In Brazil, the CAR illustrates how these tools can be misused. Originally created as a tool for environmental regularization, the CAR soon became a mechanism for the legalization of land obtained through grilagem. Its three-phase operation—self-declaration, validation, and the Programa de Regularização Ambiental, PRA (Environmental Regularization Program)—is structurally flawed. In the initial phase, the owner simply self-declares information about their property without any requirement for documentary evidence. Validation, which should be carried out by inspectors, has been replaced by an algorithmic/automated verification process. As Larissa explained, this can lead to erroneous approvals of thousands of hectares of illegally occupied public or Indigenous land. Moreover, the digital, satellite-based assessment system cannot distinguish between long-standing occupations and recent invasions—an essential distinction, given that the Forest Code granted amnesty for deforestation which occurred prior to 2008.

The situation worsened with the so-called Lei da Grilagem (Land Grabbing Law) (Provisional Measure 759/2016, later converted into Law 13,459/2017). Since this law was approved, grileiros can self-declare, via CAR, ownership of up to 2,500 hectares of public land (previously the limit was 1,500 hectares) and obtain a discount of up to 90% on land regularization if they can "prove" occupation before 2008 (or 2011 in the Amazon). Another document issued by the government upon presentation of the CAR is the Certificado de Regularização de Ocupação, CRO (Certificate of Occupancy Regularization), which serves as a "preliminary" step toward land titling. With this CRO, it becomes possible to obtain bank credit and issue green bonds tied to areas that may still be public land. The result is the conversion of public lands into financial assets, with investment funds acquiring asset-backed titles from areas that, in practice, still belong to the federal government.

This fragile digital system has generated the "Fictitious Brazil phenomenon,"24 where farms are registered on rivers, Indigenous territories, conservation units, or federal lands. GRAIN's 2019 "Digital Fences" survey—conducted with Larissa's participation25 — shows that, according to official data, Brazil had around 430 million hectares eligible for registration; yet the CAR already contained 550 million hectares. This means that 30% more land has been registered than actually exists. "The Map Biomas cross-references 18 different databases. When you combine all of them, the result is that 49% of Brazil is private land—but the CAR indicates 76%," Larissa states "So, you have a huge mess, a digital land dispute to determine what is public Brazil and what is private. And in the process, traditional territories and Indigenous lands are concealed. In 2019, only 6% of the mapped area was classified as collective territory," she adds.Gleba Tauá is a prime example of the "Fictitious Brazil" created by illegal land registrations. In this Cerrado area of the Legal Amazon—where the law requires that 35% be set aside as reserva legal—there are 93 overlapping CAR registrations covering 13,498 hectares (65% of the land). Yet only 1,883 hectares (14% of the total) are actually declared as reserva legal. The Binotto family has more than 11,000 hectares irregularly registered as their own property, leading to the deforestation of 12,334 hectares of Cerrado by 2020. This reality is sharply opposed to the legitimate use of traditional lands in Gleba Tauá.

Gleba Tauá is a prime example of the "Fictitious Brazil" created by illegal land registrations. In this Cerrado area of the Legal Amazon—where the law requires that 35% be set aside as reserva legal—there are 93 overlapping CAR registrations covering 13,498 hectares (65% of the land). Yet only 1,883 hectares (14% of the total) are actually declared as reserva legal. The Binotto family has more than 11,000 hectares irregularly registered as their own property, leading to the deforestation of 12,334 hectares of Cerrado by 2020. This reality is sharply opposed to the legitimate use of traditional lands in Gleba Tauá.26

The multiple overlapping environmental registration systems in Gleba Tauá, although illegal, remain effective in practice, since most have not been suspended or canceled. This situation ultimately legitimizes both the deforestation and the private appropriation carried out by the Binotto family. A simple cross-check between the environmental data and the land tenure information would readily show that much of the gleba (land parcel) is federal public land. This, in turn, would lead to the cancellation of the irregular CAR entries and to the formal recognition that the deforestation was illegal.

However, the persistence of these CAR registrations—together with ongoing deforestation—makes evident the State’s absolute complicity with the land-grabbing scheme that has taken root in the region. The authorities' continued inaction effectively gives tacit approval to these illegal practices.

The narrative of digital land governance therefore hides a perverse reality: self-declaratory digital systems have become tools for large-scale land grabbing, now legitimized through digitalization, algorithms, and artificial intelligence. Public lands are converted into financial assets, while traditional communities are pressured to conform to an individualist, private-property model that destroys their way of life. Yet governments and international institutions persist in treating technology as a magic solution, ignoring the fact that without real oversight and social justice, digitalization only deepens inequalities. The result is a "Fictional Brazil" where data is worth more than people, and the land—while being destroyed—is simultaneously digitized and financialized.

Regenerative technologies as a way out

Agribusiness relies on technologies designed to serve export-oriented monoculture: tools for environmental devastation, territorial violence against peoples, and exclusionary digital systems, all aimed at homogenizing production and concentrating power and profit. In contrast, social, regenerative, and ancestral technologies resist this model: knowledge systems that sustain life and biodiversity in rural territories, even in the face of agribusiness's predatory expansion.

In the Matopiba region, for example, rural communities have developed agroecological practices that directly challenge the logic of agribusiness. As Vinícius reports from working with these communities, their social technologies are often rendered invisible, even though they are fundamental to their survival. Traditional lands are not only productive units; they are spaces of hope, collective work, and projects for a free life. Recognizing these practices as legitimate technologies is essential, as they fulfill a vital social function, especially in territories that have been turned into "sacrifice zones" by the advance of capital.

Many family farmers and social movements question the imposition of digital technologies that do not address their real needs. For them, solutions such as drones or big data systems are often unnecessary, since their traditional knowledge—from managing native seeds to reading the land for planting—already meets their demands. Even in the face of climate change, which intensifies droughts and floods, these communities resort to longstanding strategies such as seed exchange networks, which allow them to adapt without becoming dependent on external technological packages.

The debate around technology in the countryside is not merely about accepting or rejecting new digital tools and artificial intelligence systems, but about more fundamental questions: what are these tools for and who controls them? While some groups resist digitization because they see it as yet another form of domination, others, such as the Movimento dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem Terra, MST (Landless Workers' Movement), seek to critically appropriate innovations, adapting them to their struggles. Partnerships with China, for example, have enabled access to small-scale machinery and bio-inputs aligned with agroecology, without compromising principles such as food sovereignty.

This diversity of strategies shows that regenerative technologies are not just technical alternatives, but political pathways. Whether through valuing ancestral knowledge or through fighting for people-led innovations, what is at stake is the construction of an agricultural model that prioritizes life, socio-environmental justice, and territorial autonomy. While agribusiness imposes its destructive logic, these experiences demonstrate that another future is possible—and is already being sown.

Bibliography

- AGUIAR, Diana; BONFIM, Joice; CORREIA, Mauricio (orgs.). Na fronteira da (i)legalidade: desmatamento e grilagem no Matopiba. Salvador: AATR, 2021.

- AGUIAR, Vinicius Gomes. Cartografia do conflito: Geotecnologia como Instrumento de luta contra o Racismo Ambiental no Norte do Tocantins. ESCRITAS-UFNT, 2023.

- ARMIERO, Marco. Wasteocene. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021.

- BRUM, Eliane. Banzeiro okotó – uma viagem à Amazônia centro do mundo. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2021.

- GRAIN and ETC Group. "Top 10 Agribusiness Giants: Corporate Concentration in Food & Farming in 2025." Grain, 2025. https://grain.org/en/article/7284-top-10-agribusiness-giants-corporate-concentration-in-food-farming-in-2025.

- GRAIN, “Techno feudalism takes root on the farm in India and China”, 24 October 2024, https://grain.org/e/7196

- HARAWAY, Donna e BRAGA, Ana Luiza. Ficar com o problema: fazer parentes no chthluceno. São Paulo: Editora N-1, 2023.

- HOPE SHAND, Kathy Jo Wetter and Kavya Chowdhry, “Food Barons 2022: crisis profiteering, digitalization and shifting power”, ETC Group, setiembre de 2022, https://www.etcgroup.org/files/files/food-barons-2022-full_sectors-final_16_sept.pdf;

- KOPENAWA, Davi; ALBERT, Bruce. A queda do céu: palavras de um xamã yanomami. Tradução de Beatriz Perrone-Moisés. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2015.

- MORAES, Antonia Laudeci Oliveira. “Dona Raimunda é que segura a gente ali na Tauá”: a trajetória de vida de Raimunda Pereira dos Santos. 2023. 150 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Estudos de Cultura e Território) – Programa de Pós-Graduação em Estudos de Cultura e Território, Universidade Federal do Norte do Tocantins, Araguaína, 2023.

- NEVES, Eduardo G. Sob os tempos do equinócio – oito mil anos de história na Amazônia central. São Paulo: Ubu editora / editora da USP, 2023.

- SANTOS, Antônio Bispo dos. A terra dá, a terra quer. São Paulo: Ubu Editora: Piseagrama, 2023.

Notes

1 ^Data from the Matopiba region and Gleba Tauá were obtained in collaboration with Antônia Laudeci Oliveira Moraes.

2 ^ BOMBARDI, Larissa. CEE Fiocruz. Brasil é um dos principais receptores de agrotóxicos proibidos na União Europeia . 2023.

3 ^ AGRISHOW. Agrishow 2025 alcança 14,6 bilhões em intenções de negócios com edição focada na pluralidade do agro . 2025.

4 ^ The internet has nothing to do with the cloud: cartografiasdainternet.org

5 ^ John Deere. Plataformas para Milho GreenSystem™ . 2025.

6 ^ The Yanomami are an Indigenous people of the Amazon, spread across more than 650 villages in a large region between Brazil and Venezuela, numbering around 40,000 individuals. With their legal reserves in the Brazilian Amazon, they are a vital people for the preservation of the rainforest.

7 ^ In Brazil, the movements of the indigenous peoples (more than 300 ethnic groups throughout the country) refer to themselves as the indigenous movement. Unlike in some Latin American countries, it is not politically incorrect to call an indigenous people "indigenous."

8 ^ EMBRAPA. O agro brasileiro alimenta 800 milhões de pessoas, diz estudo da Embrapa . 2021.

9 ^ Confederação da Agricultura e Pecuária (CNA). Panorama do Agro . 2025.

10 ^ MINISTÉRIO DO DESENVOLVIMENTO E ASSISTÊNCIA SOCIAL (MDS). Mapa da Fome da ONU: insegurança alimentar severa cai 85% no Brasil em 2023 . 2024.

11 ^ The term "quilombola" refers to a member of a "quilombo", an autonomous community founded by African descendants who had escaped slavery in their quest for liberty. "Quilombos" originated in colonial Brazil, representing powerful sites of social and cultural resistance. "Ribeirinhos/as" are also traditional communities which live on riverbanks, near streams, in floodplains, and by lagoons. Their activities include extraction, hunting, and family farming, with fishing being their main economic support.

12 ^ InvestSP - Agência Paulista de Promoção de Investimentos e Competitividade. Agrishow 2025: Maior feira do agro da América Latina encerra edição com R$ 14,6 bilhões em negócios . 5 de maio de 2025.

13 ^ Bayer e Microsoft anunciam parceria estratégica para otimizar e avançar capacidades digitais na cadeia de valor de alimentos, rações, combustíveis e fibras – 17/11/2021

14 ^

Top 10 agribusiness giants: corporate concentration in food & farming in 2025

GRAIN, “El feudalismo tecnológico se arraiga en las granjas de la India y China», 24/10/2024

Hope Shand, Kathy Jo Wetter y Kavya Chowdhry, “Food Barons 2022: crisis profiteering, digitalization and shifting power», ETC Group, septiembre de 2022

15 ^ Embrapa – MATOPIBA: sobre o tema

17 ^ Brasil de Fato, Fronteira agrícola do Matopiba é a maior área emissora de CO₂ no Cerrado

18 ^ MapBiomas – Plataforma de Monitoramento de Focos de Queimadas

19 ^ MapBiomas – Destaques RAD 2023 (PDF)

20 ^ Le Monde Diplomatique Brasil – O Cerrado como zona de sacrifício imposta pelo agronegócio

21 ^ Agro é, Gleba Tauá: luta pela terra no Cerrado tocantinense

22 ^ CPT Nacional – Acervo de Conflitos no Campo

23 ^ Governo do Brasil – Regularização Ambiental

24 ^ O Globo – Brasil fictício: propriedade de terra autodeclarada excede área do país

25 ^ GRAIN – Cercas digitais: cercamento financeiro das terras agrícolas na América do Sul

26 ^ Matopiba Grilagem – Site oficial

Translator's Note

- I. ^ The term "quilombola" refers to a member of a "quilombo", an autonomous community founded by African descendants who had escaped slavery in their quest for liberty. "Quilombos" originated in colonial Brazil, representing powerful sites of social and cultural resistance. "Ribeirinhos/as" are also traditional communities which live on riverbanks, near streams, in floodplains, and by lagoons. Their activities include extraction, hunting, and family farming, with fishing being their main economic support.

- II. ^ The term "reserva legal" is a specific legal concept in Brazilian environmental law. It mandates that rural landowners must set aside a specific percentage of their property for the conservation of native vegetation to protect natural resources, biodiversity, and wildlife.

- III. ^ "Mata em pé" literally translates to "standing forest" or "forest on foot." In Brazilian environmental discourse, it is a powerful term used to refer to intact, native vegetation that has not been deforested. The phrase promotes the idea that the environmental and long-term economic value of a forest is greater when it is preserved and left standing than when it is cleared for short-term projects such as agriculture and timber production.

- IV. ^ "Correntão" which literally means "big chain", is a large-scale deforestation method that uses a heavy, long metal chain hooked between two large tractors. The chain is dragged across the area, quickly and efficiently cutting down all vegetation—including native forest—to make way for cattle or monoculture crops.

- V. ^ The term "posseiro" (plural: "posseiros") is a term in the context of Brazilian land rights and agrarian conflict. The meaning revolves around the concept of "possession" ("posse" in Portuguese) versus legal title ("propriedade"). "Posseiro" could be a rural worker, peasant, or family who occupies, lives on, and actively cultivates a piece of land but does not hold the formal, legal deed or title to it.