Geopolitics of the end of the world: rare earths in Penco, Chile

By Paz Peña and Cecilia Ananías. Penco, CHILE.

Instituto Latinoamericano de Terraformación

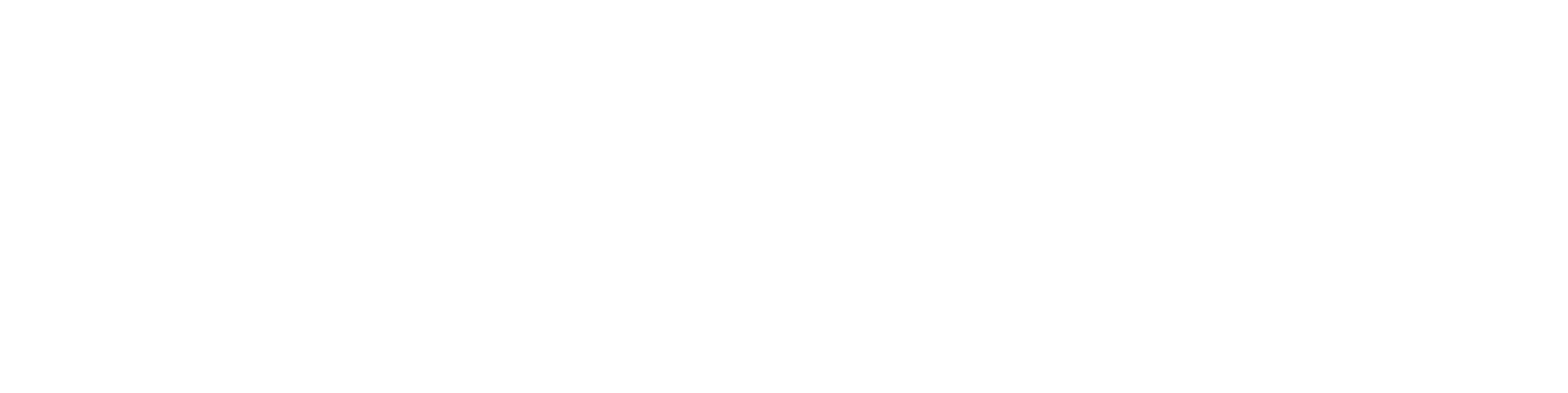

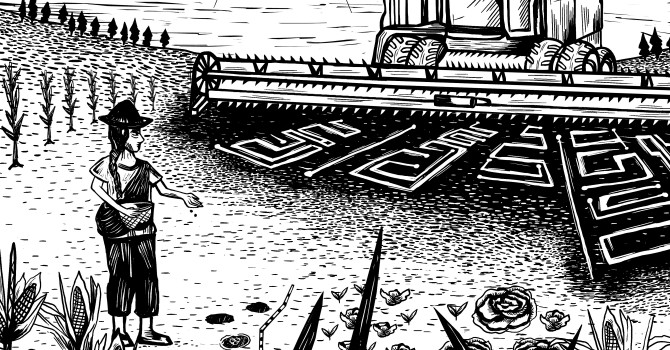

Illustrations: Giovanna Joo

MINERAL

Everything that begins as tragedy ends as a business opportunity.

In early 2025, a headline from CNBC declared: “Greenland's melting ice is clearing the way for a mineral 'gold rush'”. The report stated that the ice’s retreat—a consequence of the climate and ecological crisis fueled by industrialized nations in the 19th and 20th centuries—has uncovered a "miracle" on this massive island between the Arctic and North Atlantic: a coveted treasure trove of critical minerals, urgently needed for the renewable energy transition. The mining boom of the 21st century—despite it being one of the most socio-environmentally destructive industries—will make us "green."

Among the minerals uncovered by the melting ice were rare earth elements—a group of 17 chemical elements considered critical for at least three of the 21st century's three major, intertwined economic sectors. These include the digital industry (especially artificial intelligence, or AI), the modern military (which relies heavily on digital advances), and renewable energy. Renewable energy is particularly crucial, as it is needed not only for the transition of our economies but also for fulfilling the vast energy requirements of AI.

The problem with rare earth elements is not actually their scarcity, as the name might suggest. The core issue is that China—the West's greatest rival and the main competitor to U.S. economic dominance—controls the supply. China is responsible for 70% of global production, with the U.S. following far behind (14%) and Australia (4%) (USGS, 2023). China also maintains a dominant share in rare earth processing globally (~85%), surpassed only by Malaysia and Estonia (International Energy Agency, 2022). Furthermore, China is the largest consumer (with an apparent consumption of 150,000 tonnes in 2020), followed by Japan, the US, and the European Union (EU).

In this context, US President Donald Trump has repeatedly expressed his desire to annex Greenland: "This is about critical minerals, this is about natural resources," said Trump's national security adviser, Mike Waltz. Trump does not stop there; he also stated: "I told [Ukraine] that I want the equivalent of like $500 billion worth of rare earths, and they've essentially agreed to do that." Trump believes the US should exchange these minerals for its ongoing support of Ukraine in the war against Russia. Meanwhile, the EU is frantically searching for new rare earth suppliers, though perhaps searching in a less outrageous way, it is doing so with equal urgency.

This race involves not only unexpected players like Greenland, but also Penco—a port city of fewer than 50,000 residents on the southern tip of Chile's Biobío region. Penco holds a significant place in history, having been central to the Mapuche resistance against the Spanish conquest and later a major industrial center in the 20th century. However, its economy is now somewhat in decline and relies heavily on the extractive industry of forestry monoculture.

Over a decade, the Penco Module, a mining project by Aclara Resources aimed at extracting rare earths, has been in the planning stages. This project has drawn attention from key automotive companies, including Tesla, Nissan, and Toyota, and has fueled enthusiasm among politicians who see these critical minerals as an unparalleled economic opportunity for the nation.

Yet, this optimism stands in stark contrast to the feelings of the Penco community. In February 2022, citizen organizations held a public consultation on the Aclara Resources project, and the outcome was unequivocal. A historic turnout of over 7,400 people resulted in an overwhelming rejection, with 99% of participants voting against the rare earth mining plan.

However, the wishes of the local population have proven insufficient, and in 2025, the idea of extracting rare earths in Penco remains more alive than ever.

Turbine, battery, missile

Rare earths, along with lithium, copper, and cobalt, are essential for renewable energy and, consequently, for the urgent transition needed to mitigate global warming and finally move beyond fossil fuels. The International Renewable Energy Agency classifies a mineral as "critical" if it is vital for energy transition technologies and meets one or more of these criteria: production is limited to a few countries, extraction is significantly challenging, or quality is declining. While the exact list varies by analysis and time period, cobalt, nickel, copper, lithium, and rare earth elements consistently stand out, especially neodymium and dysprosium. Within the rare earth group, praseodymium, neodymium, terbium, and dysprosium are necessary for the permanent magnets used in wind turbines and electric vehicle motors—a fact that has made the automotive sector deeply interested in diversifying its rare earth supply. Overall, the intense demand for these renewable energy technologies accounts for approximately 91% of the total value of the global rare earth metals market.

Rare earths are equally important to the digital industry. Because of their unique physical and chemical properties—particularly their magnetic and optical qualities—rare earths are found in many components essential to digitalization, including flat screens, LED lighting, digital camera lenses, and hard drives. Even more critically, these elements are key components in the semiconductors that power artificial intelligence (AI) and data centers. Their exceptionally strong magnetic properties, excellent electrical conductivity, and high heat resistance make them ideal for specialized chips like graphics processing units (GPUs), application-specific integrated circuits (ASICs), and field-programmable gate arrays (FPGAs). Furthermore, we cannot ignore the massive energy needs of AI, which is already one of the world's largest power consumers and therefore requires significant renewable energy.

Additionally, in an increasingly digitalized world, the modern military stands out as a major consumer of rare earths. This sector depends on new technologies and continues to be a key determinant of global geopolitical power. For example, the United States Department of Defense utilizes rare earths for a wide range of applications within its weapons systems—in radars, precision-guided munitions, lasers, satellites, and equipment including night vision goggles. Magnets made from these materials can store significant magnetic energy, making them indispensable for advanced weapon systems like Tomahawk missiles, Predator unmanned aerial vehicles, and the JDAM (Joint Direct Attack Munition) smart bomb series. The F-35 fifth-generation fighter requires more than 400 kg of rare earth elements; an Arleigh Burke DDG-51 destroyer needs 5,200 pounds; and a Virginia-class submarine requires 4,175 kilograms. In short, the more advanced and technologically sophisticated military equipment becomes, the greater the variety of applications for rare earths will be in the armed forces of the future.

Simply put, challenging the supply of rare earths—so fundamental to the 21st-century's industrial engines—is a matter of survival for the West, and particularly for the U.S. in maintaining its geopolitical dominance. This challenge is underscored by China's response to the tariff war: restricting certain rare earth exports, which puts the entire U.S. military and technology industry at risk.

But Chile is not Greenland. While there is no prospect of seeking annexation to the US, American economists have cautioned Chile that negotiations over critical minerals could lead to "additional unreasonable demands" from the Trump administration. However, no dissenting argument seems to dampen the optimistic mood of Chile’s political and economic establishment. The most staunch Pinochetist neoliberal think tanks appear fearless, confidently describing rare earths as "the strategic bargaining chip with the United States" and "Chile's new wealth." In his left-wing government's 2024 public account, Chilean President Gabriel Boric referred to the national production of "copper, lithium, and other minerals critical to the energy transition" and stated: "Chile can become a global leader in both responding to climate change and transitioning to a green economy. We can't afford to miss this opportunity."

We must acknowledge one fact about energy transition: it will depend on intensive mining for at least the next 15 years. Only after this time will we likely have the political processes, practical implementation, and necessary technology to establish better mineral recycling cycles. Until that time, the debate must urgently pivot to how we can implement principles of socio-environmental justice—both nationally and internationally—in the territories currently "rescuing" the planet through these intensive mining cycles. This is particularly crucial in stable, democratic countries like Chile, where convention dictates that institutions should be at the service of the people.

Socio-environmental justice is a deeply debated issue within communities currently facing intensive mining projects—often framed as the essential key to the climate transition. Their goal is to highlight a core problem: the communities that did not create the climate crisis are now being forced to sacrifice their territories, economic and cultural activities, health and all non-human life in their habitats, all to keep the wheels of intensive capitalism turning. Therefore, concepts like "green extractivism" highlight how marginalized, low-income, and minority communities are unfairly shouldering the heaviest social, environmental, and economic costs of the energy transition—just as they did during the era of fossil fuels.

Rather than the enabling of a meaningful political conversation with these communities—one that addresses the ecological, social, and economic challenges through social justice principles and ensures that this social conflict does not endanger the urgent energy transition—we instead see economic and geopolitical pressures concerningly gaining ground. These forces seek to perpetuate the logic of pure, unbridled extractivism, which exploits the institutional fragility of these countries through lax environmental regulation, or by simply turning a blind eye to illegal mining.

What is sustainability in rare earths?

Back in 2011, the mining company Biolantánidos, a subsidiary of the Chilean conglomerate Larraín Vial, began preparations and prospecting mining for rare earths on the coast of Concepción province. In July 2016, the company submitted an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS), which was rejected that August due to the report’s failure to rule out the possibility that the mining activity would have significant adverse effects on the chemical quality of the soil and water (both surface and groundwater). Consequently, they were required to submit a much more comprehensive report—an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA).

Since the first EIS was submitted in 2018, during which time there have been several changes in ownership (the project is now controlled by Aclara Resources), the company has filed five Environmental Impact Statements (EISs)—all of which have been rejected by the environmental authorities. As of the date of this report, a new EIS submitted by Aclara in 2024 is currently under review. Although the company insists the latest project is completely sustainable, trust in Penco is severely damaged, and few residents accept this greenwashing rhetoric.

As is true for all rare earth mines, the significant socio-environmental consequences are one of the most controversial aspects. Extraction involves digging enormous open-pit mines, which can pollute the environment and disrupt ecosystems. Poorly regulated operations can create wastewater ponds loaded with acids, heavy metals, and radioactive material capable of contaminating groundwater. Furthermore, processing the raw ore into a usable form for magnets and other technologies is a lengthy process that requires large amounts of water and potentially toxic chemicals, generating bulky waste. The separation stage presents unique environmental challenges. Because rare earth elements are chemically very similar and tend to clump together, their separation requires multiple, sequential steps using a variety of powerful solvents. Caustic sodium hydroxide, for example, is used to separate cerium from the mixture.

For every tonne of rare earths produced, the extraction process yields 13 kg of dust, 9,600-12,000 cubic meters of gaseous waste, 75 cubic meters of wastewater, and one tonne of radioactive residue. This contamination occurs because the rare earth minerals contain metals which, when combined with the chemicals in leaching ponds, pollute the air, water, and soil.

In addition to concerns about heavy metals and other toxic materials in the waste, further concerns about the potential effects of radioactivity on human health continue to attract international attention. In 2019, protests broke out in Malaysia over what activists called "a mountain of toxic waste"—about 1.5 million metric tonnes—produced by a rare earth separation plant near the city of Kuantan. The plant, owned by Lynas, processes rare earth ore shipped from Mount Weld in Australia. The ore is first cooked with sulfuric acid and then diluted with water to dissolve the rare earths; the resulting waste often contains traces of radioactive thorium.

The problem is that, according to some researchers, there is still limited epidemiological evidence regarding the actual impact of rare earth mining on human health and the environment. Much of the existing evidence relates only to the toxicity of heavy metals such as arsenic. Furthermore, the low concentration of radioactive elements in the mined rare earths makes it unclear whether the concerns about radioactive waste are scientifically justified.

In this context, various scientific efforts—often funded by the mining companies themselves—are underway to mitigate these impacts. Examples include using bacteria instead of toxic chemicals to separate the metals, and extracting rare earths from coal ash rather than raw minerals. However, all these projects require further development, and it remains uncertain whether they can become a viable alternative given the enormous global demand. Similarly, while there are high expectations for rare earth recycling, it currently remains a marginal source (less than 1%). It still faces numerous obstacles, such as the low concentration of elements in end products and the inherent difficulty of separating individual elements. Moreover, recycling is far from being a clean industry in general, as it requires significant energy and generates hazardous waste.

In the face of these geopolitical disputes, any successful rare earth supplier must offer three key advantages: production outside China, traceable sourcing (i.e. not from illegal mining), and, given the industry's significant hazards, environmentally responsible mining. Aclara Resources asserts that its Penco Module satisfies all three. Unlike operations in China or Myanmar, the Penco project relies on ionic clays. According to the company, this method enables an exceptionally clean and simple extraction, promising 95% water recycling, 99% fertilizer recycling, zero liquid waste, and, notably, no radioactivity. Outside of Chile, ionic clays are only found in Brazil, Australia, South Africa, and Uganda.

However, it has been challenging to find independent media sources on this topic; most references seem to rely solely on the claims made by the mining companies themselves. Moreover, there have been few scientific studies on the sustainability of ionic clays. Amongst those are two papers published in respected journals. Both appear to reference the Penco case, and both present major benefits such as low extraction and pretreatment costs, minimal environmental and safety risks, low energy use, and high recovery of valuable heavy rare earths.[19] There are also records detailing advancements in technology designed to make the extraction of these ionic clays less environmentally damaging.[20] It is worth noting too that these studies are spearheaded by Gisele Azimi, a professor at the University of Toronto who is also the director of the mining company Aclara.[21] A conflict of interest that could be crucial.

Regardless, the socio-environmental consequences extend far beyond the immediate technical aspects of extraction and processing. A 2023 report from the Institute for Policy Studies titled "Mapping the impact and conflicts of rare earth elements"[22] identifies a common global thread: violence, criminalization, and human rights abuses. This is clearly seen in the failure to recognize the rights, traditional livelihoods, and worldviews of local communities. Furthermore, the report notes that environmental defenders are often directly targeted with threats, intimidation, and false accusations for speaking out. In addition, many of these rare earth mining projects are deliberately established in recognized protected areas or critical biodiversity hotspots. There are documented cases globally where both existing and proposed mines operate directly within Indigenous territories, putting sacred sites and other culturally significant areas at risk. That aside, there exists a lack of transparency and public consultation across the board. For example, in the cases documented by the Institute, companies often provided little or no information, blocked meaningful community input, and—most significantly for Indigenous communities—violated their fundamental right to free, prior, and informed consent.

This is the exact context in which the Penco community's resistance is unfolding.

Mining in your backyard

When I was told the rare earth mining project was near Penco, I pictured it being a couple of hills away. I was far too optimistic: when I walked to the fundo that would be affected by the project, it took me less than ten minutes on foot from the town's main square. I started the walk with a coffee in my hand, and by the time we reached the entrance, I’d taken no more than three sips. We had barely covered five blocks, all lined with small houses.

I remember standing there in the middle of the damp, reddish earth, which was so clayey and mineral, and gazing in awe: to my right was the entrance to the Fundo Coihueco (home to the Penco Module), the enormous concrete pillars of the Itata highway passing overhead, and a mural proclaiming "Penco without mining." To my left was a local school—covered in children's drawings—and a small primary emergency health service.

Even with the modifications to its plan, Aclara Resources would be right next to Penco. It was then that I finally understood the urgent resistance of the men and women of Penco to this project.

Neither so green nor so simple

"Aclara has engaged in highly questionable practices because it fails to disclose information about all the damage and consequences the project will have on the territory, and it disguises its project as sustainable," emphasizes Camila Arriagada of the local organization Keule Resiste..

On its website, Aclara Resources defines itself as a sustainable initiative and a clean, traceable, and independent source of rare earths. But it never refers to itself as a mining company. It does not even talk about extraction, instead calling the process "circular harvesting of minerals." The company, which is listed on the Toronto Stock Exchange and has the Hochschild Group as its main shareholder, constantly changes its name, partnerships, and strategy, but at its core, it always remains the same entity: REE Uno Spa (Rare Earth Extraction UNO).

The former regional councilor and Keule Resiste activist knows by heart the mining company's key argument that it will bring jobs. But she emphasizes the limited reality: the company would create only 300 to 500 temporary jobs during construction and just 200 permanent jobs, according to the latest Environmental Impact Statement. Arriagada elaborates: "What they want most is to create jobs, and that's why they're offering training courses to local men and women from the neighborhood. However, we can see that this does not compensate for the damage it will cause to the local economy. The gastronomic and tourist hub of Barrio Chino de Lirquén, the emerging gastronomic hub in Playa Negra, and even the Penco Chamber of Commerce are all against this project because of the impact it will have on our community."

Arriagada argues that a mining company will not solve unemployment and could even introduce new social problems. "From our experience in the north, we know that mining companies weaken the social fabric and bring with them issues such as drug addiction and prostitution," she adds.

Javiera Rodríguez, a sociologist at the Pongo Foundation, echoes this concern: "This occurs because mining operations involve creating 'dormitory towns' where many male workers are brought in. We already have a port [Talcahuano], overwhelmed with drugs and casinos, which harms children: mining brings a new wave of other patriarchal businesses." She concludes: "This is the mighty Goliath we are facing. And they don't operate like a forestry company or a dam: they arrive in these territories, assess the vulnerabilities of the people, and construct a social narrative that convinces people they need this work."

For the organizations consulted, the potential effects of this mining company are alarmingly broad and diverse. Their primary concern is the project's unacceptable proximity to the city, including schools, health centers, and private homes. "It has the particularity of being located on hills that are extremely close to populated areas—between one and two kilometers from the nearest town," notes Dámaso Saavedra, a forestry engineer who was part of the now-paused Keule Foundation (dedicated to studying and defending the queule tree). Saavedra, who participated in several evaluations and provided technical observations on the project, explains his position: "I have nothing against companies; I own one myself, and I've spoken with mining executives. But the core problem is that they don't listen to the people, and their chosen location is next to endangered species and too close to the urban area. We have never experienced anything like this, that is why it's causing such concern."

By endangered species, he is referring to three native trees that still survive on the Penco hills, despite the ravages of the forestry industry in the area: the naranjillo, the pitao, and the queule. The latter is likely the most urgent species to protect, as it is a living fossil that survives only in the south-central region of our country.

Saavedra explains: "The queule is a tree endemic to Chile and declared endangered. It holds the status of a natural monument, similar to the araucaria. This species is vital, yet there are few in-depth studies on the potential effects this project could have." He notes that many details putting the queule and other species at risk remain unknown: "Where exactly will the trucks travel? What is the distance between the traction points and the tree? What changes will it cause to the soil?" He stresses that the queule thrives specifically in the characteristic clay the company intends to move and exploit. "Therefore, we need to protect not just the trees, but their entire natural environment," he concludes.

Although Aclara states it will reforest the native trees that are affected, Arriagada, the Keule Resiste activist, explains the reality: "When they talk about revegetation, they fail to mention that no one can guarantee the survival of these species, nor will it compensate for the damage to existing trees. The queule, for instance, grows very slowly; here in Penco, we have very tall, ancient trees, and it is difficult to restore or repair that kind of loss."

Another core argument that activists and experts firmly refute is the company's claim that its operations will have no impact on the territory's water supply. "Aclara repeatedly states its project is sustainable, that it uses a closed circuit for water reuse, and that they'll even use wastewater," Arriagada explains. "But once they start operations, they'll still need other types of water. More critically, the pollution and intervention in the territory will inevitably impact the Penco River and other local waterways, including groundwater and springs. This is a huge concern for us because the water quality in Penco is exceptionally high."

Therefore, instead of addressing each element of the ecosystem separately, it is vital to discuss the watershed that this project would affect. . Débora Ramírez, who is part of the Manzana Verde Foundation and deeply involved in the Parque Para Penco project, explains the concept. "A watershed is a geomorphological unit, but the easiest way to understand it is to compare it to a bathtub. If you pour water into the top of the tub, it naturally flows to the center and then down the drain; the water won't climb or flow out—it will always follow the same path. In Penco, the hills act as that bathtub, forming the waterways that carry water to the sea. That is what we are trying to protect." She continues: "Currently, Penco relies on the Biobío River and the Concepción city system for water access, but that supply will run out in a few years. When that happens, the district will need its own water source, ideally our own river, which is of very good quality. Now, the mining company wants to set up operations on the upper part of those hills. Logically, everything that runs off from there will affect the watershed and the river below. It is a project entirely incompatible with Penco's freshwater supply."

For the professor, who specializes in agroecology, this is precisely where the dialogue between communities and companies breaks down: "Water is worth more than anything else. The company talks about investment with 'magic numbers,' but those figures are completely incompatible with the tangible impact of depriving a community of water."

Ramírez discusses another major impact: "The huge volume of water trucks that will be constantly coming and going, despite their claims not to use river water. The removal of debris, the resulting traffic. The infrastructure of the area cannot handle that kind of load. In addition, there would be unrelenting noise, a constant hum." As Rodríguez from Fundación Pongo adds, the project “received technical objections because they claim that around 140 trucks per hour will be leaving the site.”

And the list does not end there. It is important to note that the affected area is a historic space for many Penco residents. That is why they want to name it a park—to help protect the land. "They've clarified that they are going to fence off the perimeter of the reservoir where we plan to install the park project," Rodríguez explains. "Since it's a mining site, people won't be able to enter because it's dangerous. This is a situation that severely aggravates the impact, as the people of Penco have historically used the area for walks, jogging, swimming, marathons, and bike rides. It is also a space for Mapuche/Lafkenche prayers and collecting medicinal plants. So, this isn't just an environmental impact; the human impact would also be severe."

“One way or another, Penco Park has always existed,” suggests Débora Ramírez, coordinator of the socio-community area of Manzana Verde Foundation. "The area has a rich past," she explains. "It once had an aqueduct and a mill. Later, a forestry company preserved the native plants to maintain water production. It was also a camping area, a residential zone for workers in the fundo, and a historic corridor used by people who would travel from Florida to Penco to sell and trade their produce. It's a living space in people's memories."

In fact, Ramírez's master's thesis focused on a series of activities in the Penco river basin, which she conceptualized as dinámicas de reciprocidad (reciprocity dynamics). "Indigenous people have been talking about these dynamics for a long time, like the trafkintu—the exchange that happens when you approach a plant and ask permission to harvest its fruit, or collect lawen—or medicine," she explains. "The underlying logic is very basic: if I destroy and mistreat nature, eventually nature will give me nothing."

From this perspective, Débora identified 200 reciprocal contributions being made in the Penco River basin. "Most of these came from agroecological practices, especially from grandparents who had passed them down to their children and grandchildren," she explains. "So, this represents a true survival of memory, creating an intergenerational structure that maintains reciprocal relationships with nature."

All these dynamics—which her maps clearly summarize—include beekeeping, water and macroinvertebrate monitoring, reforestation, sharing local history, urban gardening, greeting ancestral spirits, seed exchange, gathering medicinal plants and forest fruits, defending the territory, and environmental education. All of this, she warns, is now at risk of being lost forever in the rush to sell rare earths abroad.

What survived monoculture

As our group walks the trail, my friend from Iquique—a desert city more than 2,000 kilometers north of Penco—finds it difficult to distinguish between native vegetation and forest monoculture. What is clearly invasive to me is not to her. "What is that blue-green tree everywhere?" she asks. "Eucalyptus," I reply. "And that other tall tree?", "Those are pines, also used for cellulose." She is visibly confused, realizing we are essentially surrounded and besieged by both species. "You have to look for what is resisting on the riverbanks." I explain to her.

We sit by the Penco River, and I point out the fuchsia and red colors of the chilkos sprouting at the water's edge, the medicinal matico leaves, the cinnamon and boldo bushes, and the impressive native ferns. Numerous native pollinators flutter across our path as the guides recite their scientific names.

A woman in our group tells me: "My family used to live and farm right here, in these hills. There was even a small school up here because the city was too far away back then. But during the dictatorship [The dictatorship mentioned is the military regime led by Augusto Pinochet in Chile (1973–1990)] they kicked everyone out... to make way for the forestry companies."

Our route ends at a riverbank. The team leading the group lays a yellow plastic sheet in the middle of the riverbed. They sit down to observe the emerging creatures, vertebrates and invertebrates.

I was cooling my feet in the crystal-clear water—a welcome relief from the summer heat—when I heard shouts of surprise. In a matter of minutes, they had found a tiger crab. This species is native to Greater Concepción and is so vulnerable it was actually believed to be extinct. But there it was: that little crab, a stark reminder that nature still survives in these hills, and that any project further altering the watershed puts it in grave danger.

2. A tiger crab specimen. This crustacean is not only endemic to Chile, but is micro-endemic to the city of Concepción, meaning it is native only to that specific area. It is currently a threatened species.

The one who gets tired, loses

The community of Penco and its activists are well aware of the strategies the mining company uses to establish itself in the area. "We've been doing this for ten years, and it could continue indefinitely," says Javiera Rodríguez, the exhaustion evident in her voice. "That's exactly what the companies are waiting for: for us to get tired; for the people to get tired. That's why they resubmit projects, trying to see if our resistance is still as strong." She believes Penco's success in resisting is due to the wide range of people involved in the struggle. "That's crucial, because when there's only one person, it's easier to reach them and corrupt them," she states.

The project exerts pressure and uses other tactics to camouflage itself, including constantly changing its name. While currently known as Aclara, the company has previously operated as Biolantánidos, Hochschild, and Módulo Penco. All of these aliases refer to the same entity: Rare Earth Extraction UNO, or REE UNO Spa. Rodríguez notes that, in addition to this shifting identity, the company has repeatedly engaged in manipulation and misrepresentation. They also employ strategies like visiting schools to host robotics workshops, "playing on the hopes of children and their parents," since no robots are ever delivered. "They even contacted a well-known local craftsman and offered him a monitor position to run workshops in their offices, knowing he was short on money. They've also offered money to various people. They actively target these vulnerabilities," the sociologist explains.

Today, the strategy to advance the project involves dividing the land into plots and finding an area with lower documented impact. "They specifically sought a section that fell outside the zones containing queule and pitao — native species that are protected and cannot be logged," explains Dámaso Saavedra. "While the current section does have naranjillo specimens, a species facing conservation issues, the Native Forest Law actually does allow these to be cut down. In other words, the mining company deliberately sought an area of lesser environmental value, so to speak, to launch the project."

Both he and Camila Arriagada agree that this is only the beginning: "There are no longer six mining extraction and disposal sites, but fewer. This makes it look like there's less impact on the territory, but we understand this would be just the first stage," the activist explains. "When they operated under the name Módulo Penco, we could interpret that as a sign of future expansion—that there could be a Módulo Santa Juana, or a Módulo Tomé. Our belief is that this company is planning to expand throughout the entire Biobío region, where they already have numerous studies and mining prospecting projects underway."

Simultaneously, the community of Penco is employing its own resistance tactics. For example, they directly countered the company's "Casa Abierta Aclara" [Aclara Open House] — a local space used to promote rare earth mining. "We decided to create our own open house," Ramírez says. "We featured local food tastings and mushroom picking, and it was a wonderful experience. A group of student interns helped us assemble all the informational displays, including maps and posters with key data."

Just as Aclara strategically used native tree mapping to site its project in the area with the supposed lowest environmental impact, the community is turning the company's data against it. "We use everything Aclara releases," the Manzana Verde member notes. "It's public information, accessible through the website Transparencia. We request geographic data, review it, and use it to strengthen our own park project. We've already caught them declaring trees in places where they simply don't exist, so we make sure to verify everything."

Javiera Rodríguez, who is a member of Fundación Pongo and participates in various territorial assemblies, adds: "We've carried out various activities over the ten years the mining company has been trying to gain a foothold here. We're currently submitting citizen observations, and the company is now working on its response. We also recently filed a request for Indigenous consultation." That request is extremely important because, even though the Módulo Penco project has been trying to settle in the area for years, the Indigenous consultation process was only launched in June 2024. This is despite the fact that, in Chile, such consultation is a right of Indigenous peoples and a State obligation, derived from Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization (ILO).

The Koñintu Lafken Mapu Indigenous association has also been a key actor in this territory. As Rodríguez explains, "I mention this because Indigenous communities here were dispossessed of their lands, so they formed urban networks and associations." Despite this displacement, they still use areas like the Penco basin for ceremonies and gathering medicinal plants. This means they would be directly affected by the project, a concern they raised early in the consultation process. In fact, in July 2025, the Biobío Environmental Assessment Service (SEA) extended the Indigenous consultation process for the rare earths project after identifying "significant environmental impacts" caused by the mining proposal.

The community is also conducting various activities to raise awareness about rare earth mining. "We want people to recognize the type of extractivism they plan to install in the region, because Penco is only the starting point," Rodríguez says. "Their mining concessions run from Itata to beyond Santa Juana, and from the Penco coast to beyond Tucapel. The goal is to weave this resistance together so we can effectively confront the mining company."

The idea for the Parque Para Penco emerged during a mixed territorial assembly. This campaign aims to unite residents and reconnect them with the territory where the reservoir is located. Ramírez explains that while the concept of a Penco Park is old, "today it's a mobilizing campaign. It allows us to name what was happening, to give it meaning and value."

Ultimately, we could argue that the final battle takes place in the arena of language, in the struggle over words. It is no coincidence, for example, that the men and women interviewed refer to the waterway as the Penco River, rather than the Penco Estuary. "Research indicates that people offer greater protection to a waterway when it is designated a 'river' instead of a 'stream,'" Débora notes. "We can easily make that change because Chile lacks real criteria for these designations. You have rivers like the Loa, which is massive in size but nearly dry, versus the so-called Penco stream, which actually transports significantly more water. By calling it the Penco River, we immediately elevate its value."

Unfortunately, another strategy employed by the mining company is that of silencing dissent. In February, the company's legal representative filed a protective action against two Penco residents. It accuses them of managing a social media account that has been used to launch "various attacks by third parties aimed at defaming and damaging the reputation and good name of ACLARA."

In its appeal, the mining company specifically targeted the Instagram and Facebook accounts of the Keule Resiste organization. ACLARA demanded, among other things, the deletion of "all content published to discredit ACLARA and the various individuals previously unjustly mentioned." Furthermore, they insisted that the identified individuals, Camila Arriagada and Arnoldo Cárcamo, "refrain from making any further posts discrediting ACLARA on any other social media account." On the other hand, the activists' defense attorney, Cristián Urrutia, has declared that this action is a mechanism of intimidation and censorship that violates both the Chilean Constitution and several international treaties.

The dispute was ultimately decided by the Supreme Court. In June 2025, the highest court reversed the earlier ruling by the Concepción Court of Appeals—a decision that had initially favored the company and required the activists to delete their social media posts. Camila Arriagada, one of those targeted by the company's lawsuit, viewed the reversal as a positive step, saying it was important "to make it clear that the Aclara mining company is wrong and has bad practices with the Penco community by prosecuting people who are critical of this mining project."

Only six killer naranjillos

The current Chilean government under President Gabriel Boric recognizes the importance of rare earths for the green economy, but only if they align with the left administration's environmental justice policy, which demands strict standards for water protection, biodiversity, and emissions reduction. As of this report's date, even though the Environmental Assessment Service (SEA) has not yet ruled on Aclara's new project in Penco, the Ministry of Economy has already included the company in the "Biobío Industrial Strengthening Plan." This plan aims to accelerate projects following the closure of the Huachipato steelworks—whose owner, the CAP Group, also happens to hold shares in Aclara.

In a recent interview, the company's general manager, Nelson Donoso Navarrete, expressed optimism about the project's future:"We are very much aligned with the current government, with the community, and with the regional government," he stated. "We have a project that offers tremendous environmental advantages and aligns with the need to create jobs. Therefore, we are extremely optimistic that our project will be approved by President Boric's administration."

In addition to its criticism of Chile's environmental institutions and their slow processes, the interview suggests that the mining company is willing to exploit one of the most historically sensitive issues in Chile for its own gain: the state's conflictive relationship with Mapuche communities in Indigenous areas like Penco. Donoso claims that where companies and the state fail to assert control, "the worst of society appears," allowing "drug trafficking and terrorism to take control of the communities."

Meanwhile, in the central capital of Santiago, away from the local dispute and in the midst of a tariff war, former Chilean President Eduardo Frei Ruíz-Tagle (1994-2000) spoke at the First National Infrastructure Congress of the Chilean Chamber of Construction (CChC). During his address, he provoked the audience by posing a pointed question:

"Have you heard of the word naranjillo?" he inquired. "A few days ago, I read about it in the press, so I asked national and international experts and did some research [...] The newspaper reported that this rare earth project in the Biobío region—a project which has been discussed for years and has attracted global investment—had been halted. Why? Because the Environmental Assessment Service (SEA) claimed there were six naranjillos in that area, and therefore the project was stopped."

Here, Frei was making reference to the events of 2023, when the Penco project's licensing application was terminated sooner than expected: the application had not properly considered the naranjillo specimens as required by environmental and forestry law. The former president argued that "rare earths are not a luxury, they are an aspiration for the country." He continued, "They are elements that will be part of the technology of the 21st and 22nd centuries, just as lithium was 20 and 30 years ago." He concluded his speech with this emphatic statement: "Rare earths must be exploited, and the naranjillo kills them. We cannot move forward like this."

Rare earths in Brazil

Aclara Resources, a company majority-owned by the Hochschild Group, is currently listed on the Toronto Stock Exchange. Currently, the company does not generate revenue and is focused on two development projects: Módulo Penco in Chile and a project in Brazil. Aclara plans to begin mining clay deposits in both countries by 2028.

Brazil holds the world's second-largest rare earth reserves after China, accounting for about 23% of the global total, according to the U.S. Geological Survey. "Brazil is our only hope," stated Jack Lifton, co-chairman of the Critical Minerals Institute. "Without Brazil's heavy rare earths, we cannot manufacture the magnets that power everything from electric vehicles to fighter jets. It's that simple."

Aclara officially launched its pilot plant in the city of Aparecida de Goiânia in April 2025, initiating the first stage of its Carina project in Brazil. The pilot plant received an investment of more than 30 million reais (US$5.3 million) and will process 500 tonnes of ionic clays using the company's patented Circular Mineral Extraction process; the same method used in Módulo Penco, Chile.

In Brazil, the primary frontiers for rare earth development are the states of Goiás, Minas Gerais, and parts of Bahia. While Aclara's project moves forward, other ventures are in early stages, including Caldeira (from Australia’s Meteoric Resources), Colossus (from Australia’s Viridis Mining), and Araxá (from Australia-listed St. George Mining). Currently, only one project is operational: this is owned by Mineração Serra Verde in the state of Goiás.

There are already significant concerns about the socio-environmental impact of these projects. In Caldas, Minas Gerais, the local community is already actively opposing the mining initiative from Meteoric Caldeira Mineração Ltda." As Ana Paula Lemes de Souza says: "While rare earths are marketed as a solution for the energy and technological transition, their extraction in Caldas directly threatens the most vital elements: water, soil, and air. The question hangs in the air like a warning: There is no green future that justifies ecocide"..