Mexican Silicon Valley: socio-environmental impacts of digital colonialism and acts of resistance for a dignified life

By Jes Ciacci and Sofía Enciso . El Salto, Jalisco, MEXICO.

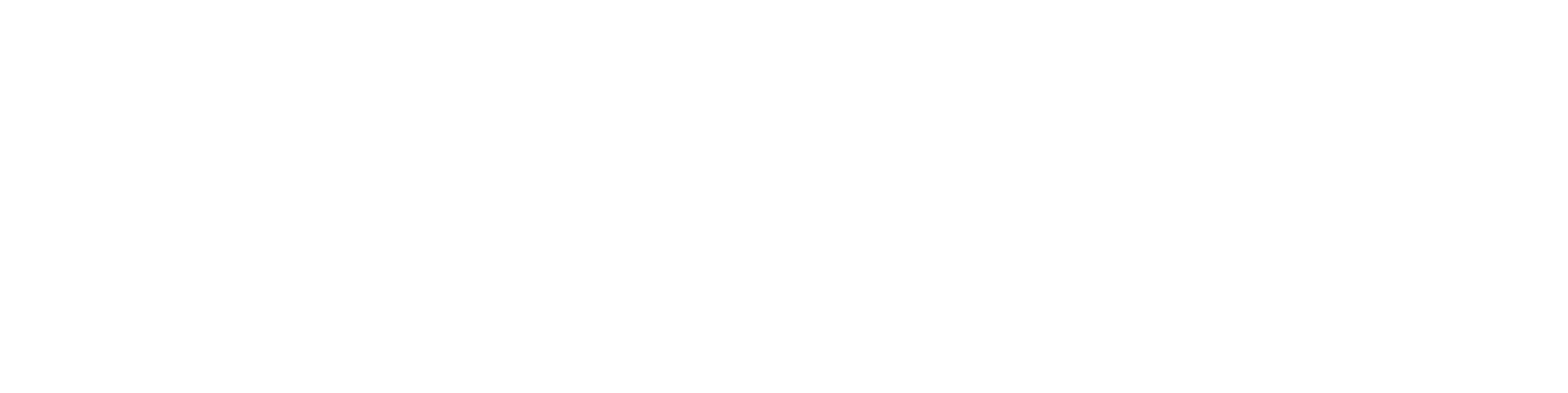

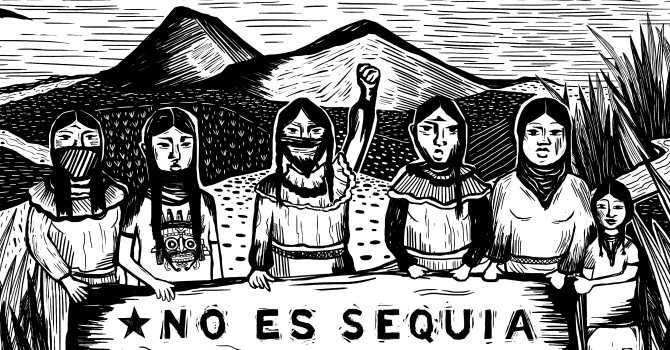

Illustrations: Giovanna Joo

AIR

Tell me what happened to you,

come on, tell me, Santiago,

when you were a source of life for my ancestors.

I want to protect you

as I defend my family,

with this rap of war

with this salto de vida.

Skool 77 - Santiago

Opening thoughts...

El Salto, located in Jalisco in western Mexico, is the municipal seat of the municipality that bears its name. It forms part of the southern metropolitan area of Guadalajara and is known as an industrial city. The town's name comes from the 18-meter waterfall the Santiago River once had in this zone. On one bank is El Salto; on the other, Juanacatlán. In the 19th century, two major projects were developed on this "Mexican Niagara": the first hydroelectric plant to supply power to the city of Guadalajara, and the largest textile factory in the state in terms of production volume and workforce. Today, 675 companies—71 of which are transnational—have settled along the river's 146 kilometers.

From a geographical perspective, this region is framed by mountain ranges, steep slopes, the Santiago River, and Lake Chapala (the largest lake in Mexico). These features, combined with the native populations' extensive territorial knowledge, served as natural barriers during the Spanish conquest. According to local legend, the invasion was only made possible by a severe drought. Several studies and newspaper articles state that the lake's first major water crisis occurred decades later, in 1953.

Paradoxically, the same geography that once protected the Indigenous Coca and Tecuexes people later went on to enable industrial development in the region: the presence of the Santiago River and the proximity of Lake Chapala provided a level of access to water which is almost unprecedented in the country:

By tracing patterns of decision-making through archival research from 1890 to the present, we observed historical milestones, including the first dam (1896), subsequent hydroelectric projects, railroad construction, and the consolidations of regional estates. We started to see how the region's current industrialization is not an isolated phenomenon but part of an enduring regional pattern, where "industrial zones" are constantly being renewed and expanded.

This is how one of the members of Un Salto de Vida (USDV), describes it. USDV is a socio-environmental collective in Jalisco composed of residents from communities in the Santiago River basin—particularly in El Salto and the surrounding area—who have been directly impacted by industrial pollution and development policies.

The "development" of this region is part of a long historical process. The Guadalajara–El Salto industrial corridor began to take shape in the early 20th century, attracting a wide range of industries from food processing to chemicals and metallurgy, and, most recently, electronics. Its expansion was enabled both by its proximity to Guadalajara and by the availability of rail infrastructure for freight transport.

Industrialization accelerated dramatically as domestic and foreign companies leveraged the region's competitive advantages and excellent land, rail, and air connections. Over the years, this area has been known as the "Mexican Silicon Valley," driven primarily by an electronics sector that competes with manufacturing hubs like China, Bangladesh, Malaysia, and Singapore.

In recent years, this technological momentum has been reinforced by narratives of "modernization" promoted across all levels of government, along with growing foreign direct investment. This is largely driven by initiatives like2025 Plan Mexico1, designed to position the country as a strategic global hub for nearshoring.2. Within this framework, El Salto stands out as one of the best located areas to attract manufacturing relocations from Asia.

At the local level, promises of modernization and development have delivered environmental devastation, severe public health deficiencies, and systematic human rights violations. This context gave birth to the Un Salto de Vida collective some 20 years ago. They defend the territory through organized anger, articulating strategies of popular resistance, political struggle, and environmental restoration.

This article outlines the historical process through which El Salto became a "sacrifice zone." It then proceeds to examine the effects of the technology industry's expansion, explore the possible impacts of Plan Mexico on the region, and document the community defense actions and territorial investigations carried out by Un Salto de Vida.

Chignahuapan, the power of nine rivers

The pollution of the Santiago River—caused by unregulated industrial and municipal waste—has become the most visible representation of environmental devastation. Dead fish, recurrent childhood fevers, and high rates of cancer and kidney failure are some of the consequences of this process (USDV Interview, 2025a). The current situation in the region is the result of a land management plan that has historically viewed the territory as an "empty" space.

With Spanish colonization, the river was renamed "Santiago" in honor of the apostle Saint Iago (known in English as Saint James) whom the colonizers entrusted themselves to. This symbolic usurpation was compounded by the suppression of the Indigenous worldview that revered the river as a sacred being. By the early 19th century, large estates had been consolidated under families which—to this day—remain connected with groups holding economic and political power. Years later, a sugar mill and a hydroelectric plant were established. This plant provided the energy needed to operate a mill for flour production. In this way, the river became embedded in new forms of political and economic organization, serving as an axis of extractive industrial "development." Industrial growth in the area advanced gradually until the 1960s, when the first industrial corridor was established, playing host to international electronics firms such as IBM and Hitachi.

The Santiago River is the second most important river in the Mexican Pacific and crosses six states (Aguascalientes, Durango, Guanajuato, Jalisco, Nayarit, and Zacatecas). For this reason, in pre-Hispanic times, it was given different names. In Nahuatl, it was known as Tzahualhuiquani, which means "the one that foams" or "the one that stirs." In oral Coca tradition it received different names, perhaps because it was tied to a fluid and symbolic worldview unique to each territory it passed through. For the groups that inhabited the El Salto region, the river was known as Chignahuapan, which means "the power of nine rivers." It was considered a living being with will, character, and energy. Its waters irrigated crops and were also an essential element of spiritual practices and collective identity. Even today, for members of Un Salto de Vida, it is a fundamental part of their identity and culture. Its contamination damages these bonds: "It is not only the river's illness, it is also our illness as a people, because our grandmothers taught us to respect the water as if it were our mother". (USDV interview, 2025a)

In addition to the cultural and spiritual relationship between the river and the communities, the water sustained their daily rural and fishing livelihoods. The river was regarded as both a collective asset and an entity with which one could communicate. Some oral stories tell of people submerging their hands or feet in the river before an important sowing, as a way of asking permission from the water spirit. Some of these historical legacies are still remembered today: "The river is no longer a river, now it is a drain. That also hurts the soul, because that is where we played, where we sowed, where we were baptized". (USDV interview, 2025a)

The (mis)named sacrifice zones

To reach El Salto, one must cross major highways and urban sprawls; the village's main avenue is a highway, too. Just one street deeper into the village, life appears ordinary, similar to any other rural town. The air, however, tells a different story: it smells like rotten oranges, burnt bones, bitter almonds, and rotten eggs. These "offensive odors," as a fanzine by the Un Salto de Vida collective calls them, are the expression of another kind of pollution.

The concept of "sacrifice zones" is not new, it was initially used during the Cold War to refer to regions contaminated by radiation and uranium mining. However, during the 1980s and 1990s—the peak of the neoliberal era—several environmental justice movements revisited the term "sacrifice zones" to denounce the inherent racism embedded within it. This logic allowed them to spatially relate the proximity of certain demographic groups to areas where soil, air, and water pollution is concentrated, being this a direct consequence of an unequal development model, and not a mere coincidence. (Tornel and Montaño 2024)

Sacrifice zones are established as regions where human and non-human populations and their ecosystems are deemed disposable. The ways of life imposed here are structural consequences of an order that prioritizes accumulation through dispossession, normalizing the production of disposable humans and territories. These are zones that exist primarily to sustain extractive capitalism, which views landscapes, plants, animals, and other elements merely as "resources" available for exploitation. These are zones where singular ways of life are imposed to conform to this hegemonic model of development. This way of thinking, deeply rooted in colonialism, justifies dispossession, pollution, and environmental destruction by regarding these zones as "empty," "underdeveloped," or "primitive."

In a 2025 episode of the Humo podcast (2025), Carlos Tornel describes "autophagic capitalism" as a system "eating itself, expanding into territories not previously considered sacrifice zones, but now necessarily designated as such by a model that must keep growing, must keep devouring." The impoverished populations of large cities—not only in the countries of the majority world but also in central European countries and the United States—are joining the ranks of the Afro-descendant, Indigenous, and rural populations that once inhabited these "empty regions." As capitalism expands, it becomes increasingly reliant on automation and the extraction of what capital calls "resources," leaving people behind and turning them into a "surplus population."

In El Salto's case, the most obvious manifestations of dispossession can be seen in the deterioration of environmental and community health—both essential to "sustaining" the country’s industrial and economic interests. From a critical Latin American viewpoint, Lopes de Souza (2020), argues, the concept of a sacrifice zone reveals how the majority world has been systematically offered up on the altar of industrial and technological development. This is not mere collateral damage; it is the result of a deliberate plan:

...they plan at the federal and even international level—with all this movement that industry is making across the territory, as if it were an empty territory containing labor, not people (...) nor citizens, since there are no rights, no responsibilities, no State, no citizen services. There are no citizens, only gente maquilada for the labor force… What is happening in El Salto is connected to a whole chain of decisions, some even made on the other side of the world. (USDV Interview, 2025a)

In these zones, violence takes different shapes, with particular impact on the environment, public health, and traditional ways of life. In El Salto, this is compounded by direct forms of violence stemming from militarization, organized crime, the criminalization of social movements, and government neglect.

If we continue to think along these lines—that we are expendable places—what does it matter if one person dies or a hundred die? What does it matter that this municipality sees the highest number of femicides, the second-highest number of disappearances, or that they chose this exact spot for the forensic cemetery? Everything is already here, why should we ruin another place? (USDV interview, 2025a)

The Observatorio de Zonas de Sacrificio (Sacrifice Zones Observatory) refers to Mapuche activist Moira Millán to explain this situation, drawing on her concept of "terricidio." This term refers to the combination of ecocide, ethnocide, and genocide in specific territories, enacted through the degradation of all forms of life in the sake of abstract progress. Sacrifice zones are also characterized by their "stolen future." For members of Un Salto de Vida, this also translates, for example, into a lack of access to school or university education, not being able to choose what they want to "do when they grow up":

...we are living a process of labor maquilación. They are beginning to technify education throughout the population, generating curricula that are specifically tailored to the needs of industrial sectors. For us, as young people, this creates cognitive precariousness (...) technical training starts at an early age, which in turn leads to a lack of criticism and shallow absorption, fostering a normalization—a dictatorship of normality—that is widespread across the territory. For us, as women, this whole process has been a constant struggle against that discourse, the one that has become an imposition on both our lives and our territories. (USDV interview, 2025a)

Lopes de Souza (2020) points out that sacrifice zones are also zones of knowledge, where people develop situated and critical interpretations of their reality, in contrast to the hegemonic knowledge that makes invisible the costs of development. In this sense, Un Salto de Vida develops a series of strategies that interweave meaning and community narratives of identity with organizational, educational, and political work, flora and fauna monitoring and environmental rescue efforts. Their body-territories are sites which enunciate and denounce environmental necropolitics. They do so from places of epistemological and situated re-existence.

To break the dictatorship of normality, to organize anger

El Salto was repeatedly referred to as "the engine of the country." The residents saw the landfill as a place of abundance, where they could find objects they otherwise couldn't afford: "For many of my generation, the existence of an industrial dump meant free stuff that we couldn't get in stores or anywhere else. The first Gatorade I ever drank came from there. Or you might visit people's houses and find electronic circuit boards thrown away by IBM that people were using as home decorations, or shiny cellophane bags that they collected to give as gifts". (USDV interview, 2025a)

The landfill was located on the Los Laureles ravine. By 2021, they managed to get it closed: this meant that garbage was no longer accumulating, but no cleanup process was carried out. "The ravine was completely filled in and is now about 50 or 60 meters higher. It is higher than the nearest hills." (USDV interview, 2025a)

This was their normality, as was playing amongst contaminated water waste and toxic, oily foam. They knew that falling there, "was a sure way to get a fever". This contamination was seen as a phenomenon that had no obvious explanation:

They didn't know where it came from. They thought of curses and shamans, but they never associated it with industrialization, because industrialization was a blessing. It gave the people quality of life, it gave them shoes, it placed their town above many others, it even meant building a nation, being proudly Mexican, doing things for Mexicans, and this feeling could not be associated with a process of death and devastation. (USDV interview, 2025a)

It was not until 2024 that the people of El Salto clearly stated their opposition to the industry. It took several years and a great deal of suffering to break with their old, long-standing normality. In just one generation, the experience of growing up and living in that same territory had been turned on its head. They began investigating, asking questions, and connecting their experiences with those of other regions facing similar situations. They started to realize these were not isolated events, but were tied directly to industrial production:

When I became more aware of this situation, around the age of 19 or 20, I started filling myself with anger, contrasting my life with the experiences of my parents and grandparents in this same place (...) It has been a long struggle to dismantle the dictatorship of normality—where smelling shit and playing in the foamy river were just daily experiences as a child. I even remember going to a clean river and thinking, 'This doesn't smell like a river.' (...) About twenty years ago, I finally connected my current reality with the stories I heard constantly at mealtimes—tales of a living territory. My grandparents and the other adults would talk about how they needed to teach me to fish, how to hang the fish, how to do things. But where are you getting your fish from now? What are you even talking about? (USDV interview, 2025a)

When the process of restoring the river first began, they discovered that there was a drain connecting the discharges into the river with the industrial zone: "'Follow the pipe', and that's exactly what we did, in that area, for years. You follow the pipe, and two kilometers away there was Honda, IBM, Hershey. That's when we began to speak out". With the complaints came criminalization and repression: "They closed the road, they started putting cameras on a wastewater outlet, following us. (We'd find) people from outside the town who were always close to us, who came (to the assemblies) but said nothing. It was this constant surveillance, and we were completely naive: 'we are friends, life is important, the territory is important, who is going to be against us when we all want a living river?'" (USDV interview, 2025a)

If I call myself a sacrifice zone

The collective Un Salto de Vida began using the concept of a "sacrifice zone" after learning about the experience of Villa Inflamable, a community located next to the Dock Sud Petrochemical Complex and the Riachuelo river basin, on the outskirts of the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires, Argentina. This area suffers from high levels of contamination from heavy metals and other toxic compounds:

The residents came up with the term "sacrifice zone" and we later had a conversation with them about how they came to identify with this label—a label which imposes ways of life and frames the territory as an empty zone. We had been talking about that (...) When they name you as a sacrifice zone, it's like an imposed erasure of who you are. But also, we saw that it allows other people facing similar struggles to quickly understand and resonate with you, that is, this term has two sides to it. (USDV interview, 2025a)

Identifying El Salto as a sacrifice zone allows them to link environmental violence to historical processes of colonization, environmental racism, and territorial dispossession. Those who live in sacrifice zones, through their struggle, generate knowledge. Through their fight for "clean land, water, and air for our peoples," they generate practices of re-existence that challenge political and capitalist impositions and propose other ways of inhabiting and caring for the world:

This continuous dialogue and community reflection is what has led us to a place of self-recognition. When the term "sacrifice zone" is imposed from outside, it carries the weight of an imposed way of life. But we have reclaimed it as a tool of defense. For us, as women, it is an act of vindication. We've taken it up so we can publicly accuse them and expose their wrongdoing. It's like we're looking for the rudest possible way to shout: 'Look what they are doing to us! This is the sheer magnitude of it, the immensity of what is happening to our lives, and we want them to solve it on that same scale'. (USDV interview, 2025a) .

Expansion of the Electronics and Technology Industry

Recent U.S. nearshoring trends, presented in 2022 as a strategy to counter "multiple threats" in Latin America—including authoritarian regimes, human rights violations, and the growing influence of the Chinese Communist Party—are directly linked to the launch of Plan Mexico, which aims to expand the regional industrial park to more than double its current size. These industrial relocation policies seek to establish the United States as a strategic and reliable partner in the region, under the premise of strengthening democracy and development. This narrative, however, repeated for decades by our northern neighbor, contrasts sharply with the actual impacts on our territories, which in many cases have resulted in consequences which are antithetical to the stated objectives. According to the Asociación de Industriales de El Salto (El Salto Industrialists Association) (n.d.):

The study and analysis of problems related to industrial activities—coupled with efforts to promote regional development—represented a turning point, leading world-class companies to set up operations and share methodology, knowledge, and technology for mass production. The resulting output became incredibly diverse, including items such as: tires, auto parts, motorbikes, circuit boards, computers, chemical and pharmaceutical products, cleaning products, tools, water pumps, glass, paper, cardboard boxes, food supplements, and pet supplies, among others.

The Mexican government maintains a "modernization" discourse that obscures the socio-environmental costs to local populations. Plan Mexico reinforces a model of reindustrialization that, according to local communities, will intensify pollution, the water crisis, and militarization of the territory. At the same time, while the electronics industries maintain a narrative of progress, environmental respect, and commitment to labor rights, the reality in the territories where they operate reveals a very different picture: disease, precarious conditions, and profound impacts on both the local population and the companies' own workers.

In this context, groups such as the Coalición de Extrabajadores(as) y Trabajadores(as) de la Industria Electrónica Nacional, CETIEN (Coalition of Former and Current Workers in the National Electronics Industry) — composed of people from Jalisco and the northern border—have, for years, been fighting for dignified and stable employment. They specifically denounce the impact of the technological industry in relation to employment precarity. Some of their experiences, collected in Inhabiting Technoaffections (2024),3 offer a vivid testimony to the tensions and damage that the current industrial model causes to bodies, communities, and territories:

The new technology means doing more with less—specifically, with less labor—which in turn means exploiting women more. As companies arrived with their new ideologies, women's wages began to fall, coupled with fewer benefits. We're very sad now because although the minimum wage has increased, those of us who used to earn more than that are now on the minimum wage. (Interview with María de Lourdes Cantor Barragan, technology industry worker in Jalisco, 2023)

While health implications soon appear:

The job requires us to carry hot molds for the circuit boards. The heat is so intense you can't even wash your hands because of the pain, and the work is also highly repetitive. This has severely affected my joints and varicose veins. I've also developed a predisposition to asthma and respiratory issues due to the fumes that you get at such high temperatures. These fumes are produced by the chemical compound used to impregnate circuit boards, allowing the liquid solder to stick. (Interview with Gisela Viridiana Rosas Moreno, technology industry worker in Jalisco, 2023)

At present, Honda is considered the most significant industry in the El Salto industrial corridor, operating a plant in Jalisco that produces motorcycles primarily for the U.S. and Canadian markets. Within the electronics sector, key companies include Flextronics (Singapore), Jabil Circuit (USA), Sanmina-SCI Systems (USA), and Plexus Electronics (USA), all focusing on assembling circuit boards, processors, and communication components. Furthermore, the corridor hosts globally recognized firms such as IBM, Hitachi, Mercado Libre, and Amazon. At the beginning of 2025, El Salto began positioning itself as a new hub for the aerospace industry, with companies like Aptiv (Ireland) and Vesta (Mexico).

Plan Mexico and future projections

El Plan México (2025) es una estrategia gubernamental que busca consolidar a México como un nodo global de producción tecnológica, mediante la expansión industrial y la atracción de inversión extranjera, consolidando a México como un destino clave para el nearshoring. A mayo de 2025 solo podemos acceder a un primer borrador, no existe un documento completo conteniendo detalles del plan. Sin embargo, es posible trazar un esquema si juntamos la información compartida por diferentes medios de prensa y anuncios gubernamentales, presentaciones en las “mañaneras” (conferencias de prensa diarias de la presidencia mexicana) y las metas, disponibles en su propia página web. Esa suma de informaciones da cuenta de la intención de reindustrializar al país a través de “polos de bienestar” que, en el entendido de integrantes del Observatorio de Zonas de Sacrificio, no son más que territorios sacrificables.

Among the key sectors identified to promote economic development and attract investments are information technology and electronics. One of the goals mentions “Increase national content in global value chains by 15% in the following sectors: automotive, aerospace, electronics, semiconductors, pharmaceutical, chemical, among others,” mostly oriented towards export. In February of this year, President Claudia Sheinbaum announced the creation of the National Semiconductor Design Center “Kutsari”, which projects its first centers in Puebla, Jalisco, and Sonora and aims to produce chips for the automotive, home appliance, and medical equipment industries, among other devices (Presidencia de México, 2025). Although there is no mention of specific companies intended to be brought to the country, there are already conversations with Netflix and Amazon Web Services (AWS), which announced million-dollar investments to establish data centers in Querétaro.

For the Jalisco Government's Coordination of Economic Growth and Development, this plan would be realized through the Jalisco Tech Hub Act. With a promise of $724 million in investment and the creation of 120,000 formal jobs by 2030, all aimed at establishing the state as a major center for innovation, talent, and high technology in Mexico and Latin America:

Jalisco is no stranger to the development of technological sectors. The history of Mexico's “Silicon Valley” began in the early 1960s with the arrival of the electronics industry, attracting companies such as SIEMENS, Motorola, and Burroughs. Today, Mexico's Silicon Valley has over 600 high-tech companies and more than 300 software and services firms, which—with the support of universities, institutions, and research centers—form a mature, interconnected ecosystem. (Government of Jalisco, 2024)

Amid rising tensions between the United States and China over the supply of electronic consumables, the municipality is expected to experience (a further) "boom" in the electronics industry:

(several industries) conducted a study and identified three potential sites around the world where those goods currently produced in China could be brought for manufacturing instead (...) The location that offered the best conditions—not only regarding infrastructure, but also concerning lower labor costs and "political diplomacy"—was El Salto. (USDV interview, 2025a)

Among the strategies aimed at strengthening and supporting the expansion project is the implementation of public policies promoting the development, retraining, and recruitment of specialized talent to meet the labor demands of companies in the industrial and high-tech sectors. Those affected by these public policies have a completely different perspective. There is a link between employment precarity and the previous restructuring of the educational system, which focused on creating "technical skills" to meet the demands of industrial plants, thereby limiting opportunities for social mobility and critical thinking.

Ignoring the demands of local populations and despite uncertainty about the socio-environmental impacts of this new industrial acceleration, Plan Mexico promises 100 new industrial parks for strategic sectors, including technology, electronics, and aerospace. In the particular case of El Salto, the aim is to consolidate it as a strategic hub for advanced manufacturing and logistics. In the last sexennial period (2018-2024), industrial land use has doubled and, according to members of Un Salto de Vida, industrial areas in the south-east of the city of Guadalajara are projected to expand by approximately 500%.

Direct affectations

(Territorial) dispossession

The expansion of the electronics industry has compounded other critical environmental problems—water and soil pollution, deterioration of air quality, and accelerated biodiversity loss—as well as the forced displacement of local communities.

What else? Well, there are eight energy megaprojects on the Santiago River. We are here to protest against the thermoelectric plant5 , but there are eight of them on the river basin. They are of different types. (...) In Jocotepec, there is another one called the Guadalajara thermoelectric plant. Then there is the La Charrería thermoelectric plant in Juanacatlán, followed by the El Salto 1 combined cycle thermoelectric plant, in El Salto. Then the Las Cuchillas thermoelectric plant in Zapotlanejo, the geothermal plant in San Lorenzo, and the geothermal plant in Ixcatán. Then, the San Cristóbal de la Barranca hydroelectric plant, the Ixtlahuacán del Río hydroelectric plant, and Canal Centenario. These are planned and are currently being built. One is finished, some are under construction, and others are on hold. (USDV interview, 2025a)

Since the beginning of the 19th century, 21 dams have been built on the river, seven of which are already operational and generate energy for industrial areas and agribusiness. This massive growth in energy projects is directly linked to the rising need for electricity to sustain the (new) industrial plants.

Militarization (territorial control)

Militarization has accompanied industrial expansion in El Salto. Since the 1990s, with the arrival of PEMEX (Mexico's state-owned oil company), military bases have been established. Recent years have seen the addition of a National Guard presence and the creation of the industrial police4 in 2023, the latter established as a government response to complaints from the industrial sector about the high level of violence and harassment from organized crime.

If you consider how the territory is divided into a triangle (National Guard base) towards Alameda and two municipalities (...) You find the airport, the high-security prison, the gasoline distribution center for western Mexico, and all the other infrastructure required by the industry. These facilities are situated and distributed according to that logic. The same applies to the communication towers, police towers, antennas—everything. (…) During the period of heavy militarization, when security forces were constantly on the streets and helicopters were circling, the forensic cemetery6 was built. The cemetery for the entire state is here, a few blocks away, and that's where all the unidentified bodies from the state, well, from everywhere, are brought, that’s why there are many caravans of (mothers) searching for the missing family members, coming from all over the country. (USDV interview, 2025b)

There are also reports of constant roadblocks, communication signal blocking, and increased surveillance, affecting the daily lives of communities:

About a month ago, they shut down all communications... there was no Oxxo, no ATMs, no bank, no cell phones, no landlines, no internet. It was as if the whole town had been disconnected. (...) In September last year, there were roadblocks, with drug traffickers burning, looting, setting fires... the whole town was disconnected, nothing worked, not even in the surrounding areas, and when the signal returned, they had killed the mayor, they had taken some homemade tanks, they had set up a sort of roadblock. (USDV interview, 2025b)

Differentiated impacts based on gender

Women carry the heaviest caregiving burden with regard to increasing kidney diseases and cancers related to pollution. They are also central to both community organization and territorial resistance efforts. Furthermore, the hormonal impacts on girls and adolescents are alarming, including cases of early puberty, endometriosis, and reproductive difficulties:

There are many hormone disruptors which are like pollutants, that can change the menstrual cycle and alter hormone levels. I don't know how it works, but something we were told in school was that the girls were starting their periods at age 7 or 8. So, there is a major disruption of the menstrual cycle due to all these pollutants. (USDV interview, 2025b)

The growing health problems were not widely discussed until the late 2000s, when the region's inhabitants began to recognize that each one of them had at least one seriously ill person in their family:

It wasn't just a problem of the smell of shit and the mosquitoes that wouldn't leave you alone; there was a disease in the population. Around that time, the governor even said that he didn't know what sin we, the people, had committed to deserve so many health and environmental problems. (USDV interview, 2025b)

It is ironic that the Jalisco government refers to the sins committed by locals while having concealed valuable information about highly carcinogenic pollutants:

A researcher from the Autonomous University of San Luis Potosí approached us to share the results of a study conducted in 2009, funded by the Jalisco State Water Commission, and was kept secret for 10 years by the state government. We found very high levels of mercury, arsenic, cadmium, lead, and some highly hazardous organic pollutants such as benzene and persistent organic compounds. These were blood and urine tests from 330 children between the ages of 6 and 12 from the municipalities of Tonalá, El Salto, and Juanacatlán. (Periodismo de lo posible, 2025)

The caregiving burden placed on women increases even further. Not only because they become responsible for looking after sick people, but also because, in many cases, men who are not suffering these impacts leave home. These are not isolated situations. That is why some women decide to organize themselves, such as the Guerreras de la 180, a group of mothers whose children are treated at the 180 clinic and who support each other in various ways:

Then they divide up the tasks: one goes to save their places in the line, another goes shopping, they take turns doing the laundry and exchange it... and also with medicines, because not everyone has access to them. So when someone gets some, they say, "Well, I have enough for 30 days, and I can give some to two or three others, and when it's their turn, they can give it back to me as a medication loan..." They lend each other dialysis bags and use a single vehicle to transport four or five patients. (USDV interview, 2025b)

The wisdom of doing: building resistances, growing life

The beginnings of Un Salto de Vida as a collective are rooted in a loving connection to their territory. From that foundation, more people joined, connections were forged, alliances proposed, and both small and large actions carried out. Life is made. An essential part of this journey involves recovering territorial identity and community historical memory through situated research based on testimonies and archival sources, generating bonds of reconnection with their ancestors, their ways of life, and the recognition of what remains alive—for example, in their traditional food practices.

The organizing process

The collective's organizing history has not followed a straight path; instead, it grew in direct response to the situations which were unfolding and the individuals or groups who reached out to them:

The years have been many and varied. Blood and sweat. One of the most difficult parts has been the openness we've collectively shown to so many people who have come here (...) Those experiences, which have toughened us, led us to establish small guidelines so we can relate to one another more clearly and take better care of ourselves. (USDV interview, 2025b)

Driven by outrage over the socio-environmental and health conditions they were facing, the organization began documenting what was happening. For years, collective members walked the territory, recording, photographing, and reporting the impacts of industrialization. With this documentation, they devised actions—denunciations—and filed amparos.

I believe that one of Un Salto de Vida's merits is that we have very diverse backgrounds. Some of us would say no, because of the institutional side, no, this would be better, no, let's do it this way. Here in the collective, there are two rules: one is that there are no rules, and the other is that anyone who proposes something has the time and life available to do it. (USDV interview, 2025b)

In previous years, a member of the collective had the idea of bringing a loudspeaker to the public square and setting it up so that people could say whatever they wanted. This practice led to community assemblies: "We spent a year in weekly assemblies, starting with four or five people and ending up with around four thousand people in the assembly." This ended with a list of demands that remains a valid document today. Among those requests for the territory were: immediate health attention, the declaration of a health and environmental emergency, restoration, recovery and clean-up of the Santiago River, protection for the hills, and a ban on industrial activity.

Today, the number of people who comprise the collective "depends on the action" being taken. There are those who join in person for every meeting, but there are also members who support from a distance yet still feel part of the community: "Something we have been learning is, as Atahualpa says, 'sing for one as for a hundred'. We do that a lot, talking one by one, by one. Also, what has helped us sustain ourselves for so long is that the people believe (...) It is more like a network of trust that has allowed us to sustain ourselves and move forward."

Only one workline: the river

Having a clean river is the common goal. And to go back to having a clean river, we need to think about every part of its territory, get to know them, think about its mountains, its air basins, its soils and sediments, its animals.

They began exploring the river through its cleanest tributaries, mapping its streams and creeks, and researching historical water levels. The river is considered together with its atmospheric basin: "Since there are many pollutant emissions and pollutants evaporating, there is also an impact on the air. Therefore, the air is an element that must also be clean and cannot be separated from the water. That is why our motto has always been clean land, water, and air for our communities. Because that is how this all exists together." One consequence of recovering the basin was that the community was able to start growing an abundance of food. This is how the nursery for planting guava, mango, and other fruit trees came into being:

We began to ask: what does sanitation mean? The first step is to stop pollution. How can you clean up if you keep contaminating? And once sanitation has taken place, there must be restoration, recovery, and conservation. In other words, it is a process, and each word we have pushed the State to adopt requires a change in its ways of thinking about the territories—this is something we, as women, have brought to the forefront, so to speak. This is not it, this is what needs to be done... We began to point out that it wasn't just a matter of declaring a health and environmental emergency zone, but of stopping decisions from being made as if it were a sacrifice zone. (USDV interview, 2025b)

Strategies for strengthening and action

Community strengthening takes shape through a wide range of actions. Territorial defense is rooted in collective memory, advanced through community reforestation and urban nurseries, and reinforced through environmental education campaigns in local schools. These campaigns use playful and educational tools to raise awareness among children and teenagers about the environmental problems affecting the Santiago River.

Over the years, they have promoted a sistematiz-acción to systematically organize and record the different areas they document. For example, in their community monitoring of wildlife and birds, they carry out systematic observations and keep records of local animal and plant species, including both migratory and resident birds. These activities are carried out in collaboration with scientists who are allied with the cause. They also promoted a community-based socio-environmental monitoring laboratory that allows residents to monitor the quality of water, air, and soil in their environment. Through this space, locals combine their expertise with scientific knowledge to generate their own data in support of environmental justice demands. This community research has provided the basis for practices that allow offensive odors to be identified: “These are odors that violently intrude on our daily lives, damaging our physical, mental, and emotional health, and preventing us from living together in harmony.” Through brochures and an online form that “volunteer sniffers” can complete, an odor monitoring system is being developed to build a map. “With this tool, we will be able to locate the emission points of what harms us and propose solutions to improve life in the places we inhabit.” (USDV interview, 2025b)

One of their transversal strategies is to connect with networks and other territorial processes at the local, regional, and international levels in order to exchange experiences, knowledge, and strategies for defending the territory and environmental justice: "It has more to do with a peer-to-peer process—with other peoples, other communities, other networks where we shape spaces, dreams, hopes, actions, and it's about strengthening each space, going back and forth between them, as if we were a single region, a single territory." The connection with academia and social organizations is "more thoughtful," "more orderly":

All binding relationships must be relevant and serve the interests of the community rather than those of individuals or external groups, and they must be directly related to the objectives of the struggle. Any process carried out with these partners must be accessible, and all information generated throughout the collaboration must be open, available, and, we could say, co-constructed. Whenever possible, the process should be built collectively, including the ways of doing and thinking, the methodologies, how decisions are made, and how the work is positioned politically. We demand that this be fully reciprocal. (USDV interview, 2025b)

In addition to political advocacy and strategic litigation through amparos, they create awareness-raising campaigns, documentaries and videos, infographics, brochures, and other materials. They have also mobilized through marches, sit-ins, and press conferences. Among the most impactful of their social advocacy actions is the Horror Tour, a guided tour of contaminated areas of the Santiago River and its surroundings, the great waterfall, and the community nursery. This tour is a powerful educational and political tool because it allows people to experience both the gravity of the situation and the power of resistance.

Among the collective's most recent strategies is community security and accompaniment, which has become necessary due to increased criminalization, harassment, and insecurity.

...Closing comments

Life experiences in the "Mexican Silicon Valley" brutally expose the impacts of a development model based on industrial and technological expansion. Against the official narrative, which is repeatedly couched in the language of "progress" and "modernization," committed journalists, academics, civil society organizations—and fundamentally, the local population organized with the Un Salto de Vida collective—are rising up from a place of anger. In doing so, they continually reinvent ways to articulate resistance based on territorial defense. These are strategies rooted in care and collective identity, in ancestral ties and the community bonds that are deeply connected to the land and the water, in strategic litigation and peaceful direct action, and in their desire for a dignified life.

The point is not to simply change the country's productive or energetic matrix to accommodate a new logic of unlimited growth. Instead, it is about making room for a change in the social matrix—in thought and action—to place other ways of being and doing at the center, even within electronic production and digital technologies. Capitalism does not accept negative responses or rejection; it imposes itself with or without consent. Perhaps that is why the defense of collective processes and the social ownership of land are fundamental as anti-capitalist strategies.

In the context of Plan Mexico, the challenges are enormous: to halt the industrialization and the normalization of viewing zones, people, and non-human beings as expendable; to stop the deepening of social precarity; to combat militarization; to demand the recognition of other economic models and ways of life that do not involve the sacrifice of the many for the benefit of a the few—an ever-decreasing few. In this sense, the alignment of digital, environmental, and human rights is urgent. But how? We commit ourselves to forms of hope sustained by the power of walking other ways of life; a politicized hope that is tied to acts of resistance in the face of what seems like an inescapable destiny. A hope unafraid to name historic and current structural inequities and to highlight differentiated responsibilities. A hope that builds and never stops imagining a future where happiness, life, and dignity return.

If the future has no future, the present becomes unnecessary. As Layla Martínez writes in her book Utopía no es una Isla (Utopia Is Not an Island): "If we only imagine a worse future, the present will seem acceptable to us and we will not fight to change things." We are about to reforest the imagination and sow the present actions that infect us with these politicized hopes. "We want nothing, just to live. We have a right to it. And this territory will have to change."

Notes

1 ^ Plan Mexico is a government initiative led by Claudia Sheinbaum and presented in January 2025. Its goal is to position the Mexican economy among the ten largest in the world. According to the information available so far, the plan seeks to promote the domestic production of 50% of the goods consumed within the national market, establish 100 industrial parks across different regions of the country, and position Mexico among the top five tourist destinations worldwide.

2 ^ Nearshoring is a business and commercial strategy that involves transferring production processes to nearby countries. Its primary goals are to reduce logistics costs, shorten delivery times, and mitigate risks arising from disruptions in global supply chains by lessening dependence on distant suppliers. In the places where it is established, however, nearshoring tends to intensify extractive dynamics, leading to increased employment precarity and territorial disputes.

3 ^ The Tecnoafecciones project proposes reimagining technologies from a feminist, decolonial, and situated perspective, with the aim of generating thought-in-action regarding our relationships with and through those technologies. It considers technological geopolitics, the processes associated with technological development, and the affects that are intertwined in our sociotechnically mediated relationships.

4 ^ According to a statement issued by the organized communities of El Salto and Juanacatlán, cited by the independent media outlet Somos el Medio, the El Salto 1 thermoelectric project is being promoted by the company Ad Astra Energía, part of the VAZ Group, which has links to the multinational corporations Anschutz Corporation (hydrocarbons) and Sprint Corporation (telecommunications). "The project plans to operate with a gross capacity of 552.32 megawatts, using methane gas extracted through fracking in Texas and transported via the Villa de Reyes–Aguascalientes–Guadalajara gas pipeline. The plant would be installed less than one kilometer from the Atequiza electrical substation and near high-risk companies such as Quimikao, Mexichem, ZF Suspensiones, RECAL (Aceros Corey), and Corporación de Occidente (formerly Euzkadi)." (Marlo, 2025, for Somos el Medio)

5 ^ A security force unique in the country, designed specifically to safeguard companies in the industrial corridor and protect both their workers and the civilian population in surrounding areas. It was developed in collaboration between the El Salto City Council and the El Salto Industrial Association (AISAC).

6 ^ The El Salto forensic cemetery is a site designated for burying unidentified bodies and bodies that have not been claimed by their families. It functions as an extension of the forensic medical service. At present, it is facing a severe overcrowding crisis and is regarded as a critical indicator of the shortcomings in the forensic system and in the institutions responsible for addressing cases of missing persons.

References

- Alam, Shahidul. (2008). Majority World: Challenging the West’s Rhetoric of Democracy. Amerasia Journal, 34(1), 88–98.

- Ciacci, J., y Ricaurte Quijano, P. (2024). Habitar las tecnoafecciones.

- El Informador. (2023, febrero 3). El Salto estrena modelo de Policía Industrial. El Informador.

- El Informador. (2023, octubre 3). El Salto es el motor de la industria en la metrópoli.

- Encizo Rivera, Enrique. (2022, marzo 4). La conquista de los ríos: Obras hidráulicas y devastación ambiental. Seguir en la Tierra.

- Entrevista USDV. (2025a). Transcripción de entrevista realizada a Un Salto de Vida, marzo 2025.

- Entrevista USDV. (2025b). Transcripción de segunda entrevista realizada a Un Salto de Vida, marzo 2025.

- Estrada Gómez, D. (2025, mayo 7). El Salto, Jalisco: Un polo emergente para la industria aeroespacial. Líder Empresarial.

- Gloss Nuñez, D. (2022). Emociones y medio ambiente: Defensa del territorio y disrupción del apego al lugar [Cap. 8].

- Gobierno de Jalisco. (2024). Política pública Jalisco Tech Hub Act. Secretaría de Desarrollo Económico del Estado de Jalisco.

- Greenpeace International. (2012, diciembre 10). Un Salto de Vida (A Leap of Life) (Excerpts) [Video]. YouTube.

- Humo. (2025, abril 29). T2 Especial: Nuestros sueños no serán su sacrificio [Audio podcast]. Spotify.

- Hernández González, E. (2015). La lucha por la justicia ambiental en Jalisco: Un Salto de Vida por la defensa del Santiago.

- ICEX. (2025). Plan industrial del sexenio de Sheinbaum 2025.

- Jabil. (s.f.). Ubicación: Guadalajara, México.

- La Verdad Noticias. (2025, enero 15). Plan México: ¿Promesa de potencia o regreso al pasado?.

- Lopes de Souza, M. (2020). ‘Sacrifice zone’: The environment–territory–place of disposable lives. Community Development Journal, 56(2), 220–243.

- Losoya, J. (s.f.). Grassroots planning in El Salto, Mexico.

- Marlo, M. (2025, 27 de mayo). Habitantes de El Salto denuncian megaproyecto termoeléctrico: “Pretenden seguir tratándonos como zona de sacrificio”. Somos El Medio.

- Martínez, L. (2020). Utopía no es una isla: Catálogo de mundos mejores. Episkaia.

- Medina Pineda, S. (2023). Historia socioambiental de Un Salto de Vida y del territorio.

- Muñoz, G. (2016, octubre 3). “A la par de la lucha y la confrontación construimos el mundo que queremos”: Un Salto de Vida. Desinformémonos.

- Periodismo de lo Posible. (s.f.). T2 Ep 5 Jalisco: Un vivero comunitario para defender el río y la vida.

- Romo, P. (2024, febrero 6). Corredor industrial de El Salto prevé atraer inversiones por 600 millones de dólares. El Economista.

- Suárez, K. (2025, enero 13). Sheinbaum presenta el Plan México para lograr inversiones de hasta 277,000 millones de dólares en México. El País.

- Tornel, C., y Montaño, P. (2024, agosto 20). La otra cara del desarrollo: Las zonas de sacrificio en México. Avispa Midia.

- UDGTV. (2018, julio 9). Las 21 empresas en Jalisco ubicadas entre las 500 más importantes de México.

- Un Salto de Vida. (2023). Relatos del río herido. Publicación comunitaria.

- Un Salto de Vida. (s.f.). Olores ofensivos en El Salto y Juanacatlán. Publicación comunitaria.